Intro

For the last four weeks, I’ve been asking the question, “Was Jesus political?”

The point of this series hasn’t been to politicize Jesus or to make Jesus the mascot for an agenda. The point has been to stop and think about how Jesus’s politics as recorded in the Bible might challenge the polarization in contemporary culture and point us to new possibilities for organizing our communities. What if Christian politics began with Jesus rather than the camps and categories of our culture war?

Like Hannah Arendt, I find an incredible “originality” in Jesus’s life and work, and I believe Jesus can cast a new vision with energizing hope for our political life. When Christians confess “Jesus is Lord” (Romans 10:9), what are we actually signing up for?

1. Economic and Political Reversal for the Poor and Oppressed

In “Mother,” I argued that Jesus was conceived, born, and raised by a radical young woman who sang songs of economic and political reversal against the system that oppressed and impoverished her. Rather than a blank slate or neutral newborn, Jesus came into the world and was educated by Mary’s passionate hope for God’s liberating kingdom.

Then, from the start of his ministry, Jesus boldly echoed his mother’s singing in word and deed. For example, in his first public message, Jesus declared that the poor, the hungry, the weeping, and the hated are “blessed” – specially favored and chosen by God for happiness. “Great is your reward in heaven,” Jesus said, insisting that God’s value-system ultimately decides the shape of reality (Luke 6:20-21). But the rich, the well-fed, the self-contented, and the famous receive only “woe” from Jesus. He says that they’ve already gotten their luck and shouldn’t expect more from God when the kingdom finally comes (6:24-26).

This theme of economic and political reversal is a red thread throughout Jesus’s teaching. “Are you envious, because I am generous?” Jesus asks in a parable about four men who worked unequal hours but received equal pay. “So the last will be first, and the first will be last” (Matthew 20:15-16).

This saying, often repeated by Jesus, gives us the key to how Jesus thinks God’s kingdom operates. In a patronage culture of wealthy lenders and indebted borrowers, Jesus unpacks his logic and declares,

But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves… I am among you as one who serves. (Luke 22:26-27)

Unsurprisingly, Jesus declares that the kingdom of God belongs to children – the most disadvantaged and endangered members of his society (Luke 18:16).

We see this reversal play out in almost every encounter Jesus has with people. For example, when Jesus visits the rich and powerful Zacchaeus (“a chief tax collector”), metanoia (worldview reversal) happens and Zach declares the unthinkable:

“Look, Lord! Here and now I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anybody out of anything, I will pay back four times the amount.”

In response, Jesus declares, “Today salvation has come to this house!” For Jesus, status-reversing generosity and justice was a sign of “salvation” – that state of perfect security with God and others that never ends. But not everyone was happy. Luke tells us that “all the people” felt threatened by this reversal, presumably because they both hated and envied Zacchaeus for his powerful wealth, which he now cuts in half and subjects to reparation (Luke 19:1-10).

The implication is clear: God’s kingdom prioritizes the downcast, the losers, and the left out. Those who want to be part of God’s kingdom must have the same priority. Politics that doesn’t exercise power and organize relationships for the poor and oppressed can’t claim to be Christ’s politics and still requires metanoia.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer captured Christ’s vision in one of his earliest lectures on “Jesus Christ and the Essence of Christianity.” When we look at Jesus’s birth and ministry,

“All traditional values seem to topple, to be revalued… Here the light of eternity falls upon that which is eternally disregarded, the eternally insignificant, the weak, ignoble, unknown, the least of these, the oppressed and despised; here that light radiates out over the houses of the prostitutes and tax collectors… here that light pours out from eternity upon the working, toiling, sinning masses…

Christianity preaches the infinite worth of that which is seemingly worthless and the infinite worthlessness of that which is seemingly so valued. What is weak shall become strong through God, and what dies shall live.”

(Bonhoeffer, 1928)

2. Counter-cultural Hospitality for Outsiders and Enemies

In “Birth,” I argued that Jesus was surrounded by outsiders and infidels from the beginning of his life and that he went on to create a community of counter-cultural hospitality.

Jesus’s first visitors were shepherds, young men at the bottom of the economic and political hierarchy, who then become Jesus’s first ambassadors. Astonishingly, his first official guests were “Magi from the east,” foreign infidels whom the prophecy-trackers of Jesus’s day expected the Messiah to destroy. But far from destroying them, Jesus’s family welcomes these national enemies, and they end up saving Jesus’s life through a courageous act of political disobedience to a violent ruler. Even so, Jesus himself becomes a political refugee in a western country during his childhood before returning home.

These formative experiences shaped Jesus’s politics for the rest of his life. Perhaps unsurprisingly in light of his background, Jesus went on to earn the notorious reputation of being “a friend of sinners and tax collectors” (Matthew 11:19). Breaking untouchable taboos, Jesus would talk with women in public and defend them from Taliban-style executions in the name of God’s law (John 4 and 8:1-11).

Perhaps most scandalously, Jesus embraced Samaritans, spent time in Samaria, and made a Samaritan the hero of his most famous story. Samaritans were triple enemies to the Jews due to their ethnic mixing, religious heresy, and political separation. John tells us that Jews wouldn’t even drink from a cup that a Samaritan had used; any contact with Samaritans was considered disgusting and dirty (John 4:9). This helps us appreciate just how extraordinary it was that Jesus befriended Samaritans and made a good (!) Samaritan the hero of his story in a conversation with a Jewish leader about what it means to be saved (Luke 10:25-37). In the typical Jewish mindset, there was no such thing as a good Samaritan. But Jesus thought there was – someone who sees and serves the abused.

Jesus’s final border-crossing, world-embracing commission to his disciples was the climax of his entire life: “Go and make learners of all nations [ethnoi], baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:19-20). This was not the sinister start of an imperialistic, colonial crusade. Jesus’s “Great Commission” was a counter-cultural call to transgress the manmade political boundaries and ethnic hostilities of the world. Its purpose was to introduce a new way of life for all people marked by obedience to Jesus’s radically inclusive commands like, “Love your enemies” (Matthew 5:43) and “Treat others the way you want to be treated” (Matthew 7:12). Jesus’s Great Commission was originally an ethical revolution defined by his shepherd-welcoming, infidel-embracing kingdom.

The clear implication is that Jesus’s kingdom is for all people united in equal value and a call for profound change in the way we live. From his birth to his final commission, Jesus’s politics could never be nationalistic or tied to the idea that one group has special favor over another. Jesus’s kingship is “good news for all people” (Luke 2:10).

The Epistle to Diognetus is one of the oldest Christian documents from the second century. And it captures this border-crossing hospitality brilliantly as it explains “the love which they [Christ-followers] have for one another, and why this new race has come to life at this time.” Unpacking this “new race” (neither Jew nor Greek but human), the letter continues,

“Come then, clear yourself of all the prejudice which occupies your mind, and throw aside the custom which deceives you, and become as it were a new person from the beginning, as one who is about to listen to a new story… For the distinction between Christians and other people is neither in country nor language nor customs. For they do not dwell in cities in some place of their own, nor do they use any strange variety of language, nor practice any extraordinary kind of life… nor are they the advocates of any human doctrine as some men are. They live in Greek and barbarian cities. They follow the local customs, both in clothing and food and in the rest of life. Yet they show forth the wonderful and confessedly strange character of the constitution of their own citizenship. They dwell in their own fatherlands but as if foreigners in them; they share all things as citizens, and suffer all things as strangers. Every foreign country is their fatherland, and every fatherland is a foreign country… They love all men and are persecuted by all men.” (II, 355; V, 359)

This “new race” embodied the multicultural, humanity-uniting movement Jesus started and wanted to spread throughout the earth through his followers. From his birth onward, Jesus’s politics indeed founded a “wonderful and confessedly strange” “constitution” and new vision of “citizenship.”

3. Prophetic Critique of Power for Human Dignity and Liberation

Then, in “Hero,” I argued that Jesus’s hero was a prophetic public enemy who was executed for his calls to radical generosity and justice and his public critiques of political corruption. After John’s arrest and brutal execution, Jesus boldly took up John’s message of metanoia (worldview revolution) word-for-word and defiantly declared John to be the greatest man in history. Jesus’s followers even started baptizing people like John did. Imagine the risky audacity.

Nonetheless, Jesus provocatively adds, “Yet whoever is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than John” (Matthew 11:12; Luke 7:28b). This points us back to the centrality of status reversal in Jesus’s politics. The losers are the winners in God’s kingdom. John’s greatness was his rejection of greatness for generosity and justice, which he embodied with his symbol of personal liberation – baptism, a complete reset in how we think and live to start over in God’s way.

Given Jesus’s hero, we shouldn’t be surprised by the audacity of Jesus’s preaching and practice against corrupt, violent power for a new way of courage and dignity. Let me give you a few thought-provoking examples.

A. When the religious leaders tell Jesus that Herod wants to kill him (apparently for following in John’s footsteps), Jesus publicly insults Herod as “that fox” – a selfish, predatory animal – and refuses to stop his work (Luke 13:32).

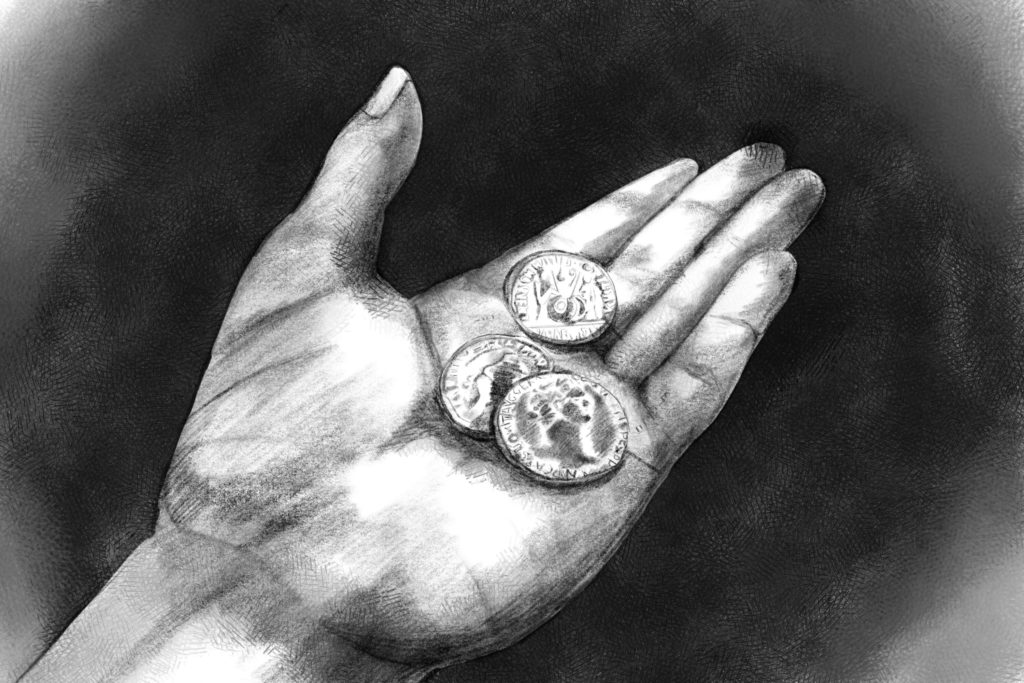

B. When Jesus is asked about paying taxes to Caesar, he gives a cryptic but subversive answer about the limits of political power. The logic goes like this: (1) coins bear Caesar’s image,

but (2) people bear God’s image (Genesis 1:26), so (3) Caesar is attacking God himself if Caesar asks for ultimate allegiance or defaces one of God’s image-bearers.

Jesus’s coded logic helps us to understand that “give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s” was not a conservative endorsement of the status quo. Nor was Jesus divorcing politics and religion. Jesus was subtly but explosively insisting that Caesar is owed no ultimate obedience and that faithfulness to God’s image may require protests far more radical than not paying taxes. It’s like Jesus says, “Caesar can have the tips, but I’m claiming the whole restaurant, and he’ll be fired if he disrespects a customer.”

This is why Matthew, Mark, and Luke each record that the crowds were “astonished” by Jesus’s statement (Matthew 22:22; Mark 12:17; Luke 20:26). With brilliant brevity, Jesus defines the limits of political legitimacy and gives us the foundational question for thinking about taxation and the other practical matters of politics: Is God’s image in people being respected or not? If it isn’t and corruption becomes severe, we should probably make whips, go into the temples of our society, and overturn the tables like Jesus did – possibly twice (Matthew 21:12-13; Mark 11:15-18; Luke 19:45-46; John 2:13-22).

C. Likewise, after Jesus’s arrest (Jesus was arrested), Pilate interrogates Jesus and asks, “Are you the king of the Jews?” and Jesus answers, “Everyone on the side of truth listens to me” (John 18:28-38). The fierce brilliance of Jesus’s answer is this: authentic political power is based on truth rather than force. Yes, Pilate could interrogate and kill Jesus. But that doesn’t mean that Pilate is really king or that his kingdom has genuine authority. It’s passing away.

Thus, when Jesus defiantly tells Pilate, “My kingdom is not of this world,” Jesus wasn’t divorcing faith and politics or saying that his kingdom is “nonpolitical.” Jesus was saying that his kingdom has a totally different source and structure than Pilate’s brutal state with its arrest, torture, kangaroo court, and killing. Jesus’s kingdom comes from transcendent truth and nonviolent dialogue. Against this, violent force and death-threats have no power.

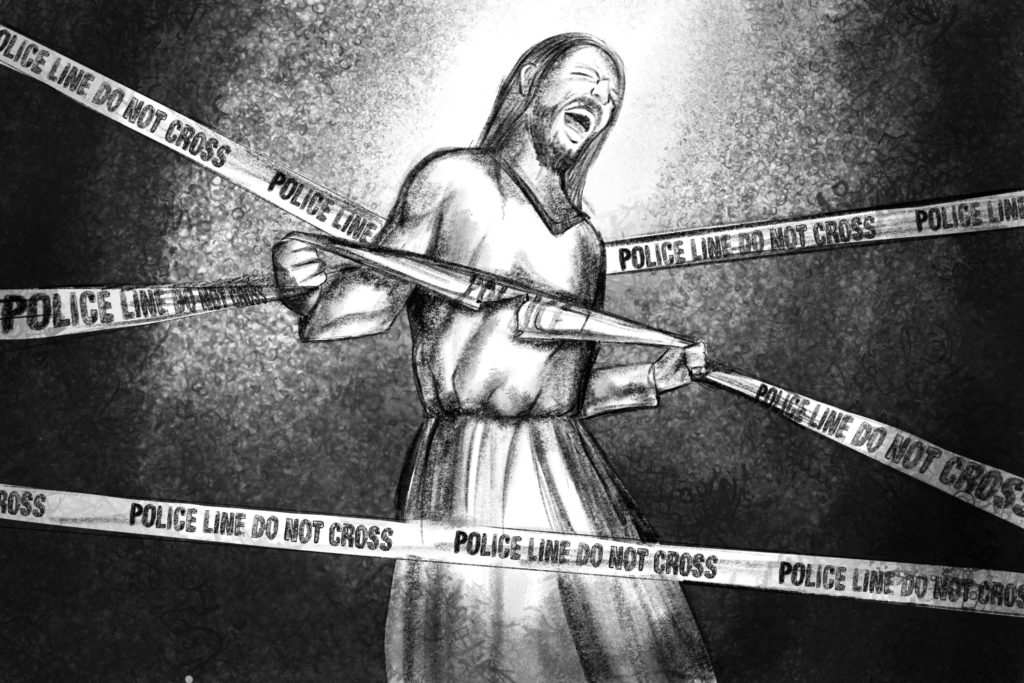

D. Finally, the Gospels want us to see Jesus’s resurrection as the ultimate overturning of political injustice and violence. After Jesus’s murder and burial, Matthew tells us that Pilate “made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting the guard” (27:65). The Roman seal was inviolable, and the Roman guard was the embodiment of the state. Think of police tape today that says, “POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS.”

But then Matthew tells us that an angel from God “rolled back the stone and sat on it… The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men” (28:2-4). Matthew is being brilliantly sarcastic and making a subversive protest: God will roll back and sit on whatever the powerful consider to be sealed and untouchable. In the presence of God’s death-defeating life, states defined and defended by injustice and atrocity will fall apart and no longer function. The tomb of death has been broken open by King Jesus.

But then Matthew tells us that an angel from God “rolled back the stone and sat on it… The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men” (28:2-4). Matthew is being brilliantly sarcastic and making a subversive protest: God will roll back and sit on whatever the powerful consider to be sealed and untouchable. In the presence of God’s death-defeating life, states defined and defended by injustice and atrocity will fall apart and no longer function. The tomb of death has been broken open by King Jesus.

Thus, even the resurrection is a political statement which completes the path John paved for Jesus and his kingdom: when you embrace metanoia, get baptized, and sacrifice your life for God’s generosity and justice, not even the most powerful empire on earth can kill or contain God’s will for life and freedom, so don’t be afraid. The climax of Jesus’s life was the embodied crescendo his mother’s song: “God has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things but has sent the rich away empty.”

Bonhoeffer powerfully captured this pillar of Christian politics in a sermon from London soon after Hitler came to power:

“Christianity stands or falls with its revolutionary protest against violence, arbitrariness and pride of power and with its apologia for the weak. I feel that Christianity is rather doing too little in showing these points than doing too much. Christianity has adjusted itself much too easily to the worship of power. It should give much more offense, more shock to the world, than it is doing. Christianity should take a more definite stand for the weak than to consider the potential moral right of the strong.” Bonhoeffer

The clear implication is that Christian politics must have the courage to follow John and Jesus in critiquing and challenging corrupt, oppressive power, even if it is counter-cultural and costs us our lives. True heroism is not found in fantasies of “greatness” defined by wealth and power like Herod, Pilate, Caesar, and the rulers of our day. True heroism is found in a life of radical generosity and justice for “the least.” And if we get crucified for it, God will roll back the stone and break the seal of violence.

5. Conclusion

So much more could be said in response to the question, “Was Jesus political?” But I hope these short essays have made you stop and think about Jesus, Christianity, and contemporary politics in new ways. Whether we like it or not, Jesus was and remains political.

Rather than offering “easy answers” or “half-baked solutions,” I’ve tried to dig into the fundamental values that Jesus embodied, preached, and practiced from his birth to his final commission. And what I’ve argued is that we find these three pillars throughout Jesus’s politics:

- Economic and political reversal for the poor and oppressed.

- Counter-cultural hospitality for outsiders and enemies.

- Prophetic critique of power for human dignity and liberation.

To confess “Jesus is Lord” is to sign up for these values and a practical commitment to implementing them in how we exercise power, organize relationships, and shape the life of our society today.

A new beginning for Christian politics is possible, and it can be good news for all people. But we need patience and courage to start with Jesus rather than the polarized categories and camps of our culture war.

“Think in new ways. The kingdom of heaven is near.”

Stop & Think:

- In what ways does Jesus’s politics challenge both sides of the Republican and Democratic polarization today?

- If Jesus’s politics doesn’t fit into our “us vs. them” binary, how can Christians become sources of new imagination for public life and envision third, fourth, and fifth options for a more just and generous society?

- Imagine practical ways to make status reversal, hospitality for outsiders, and liberation part of your everyday life. Write down a few ideas and try them out this week.