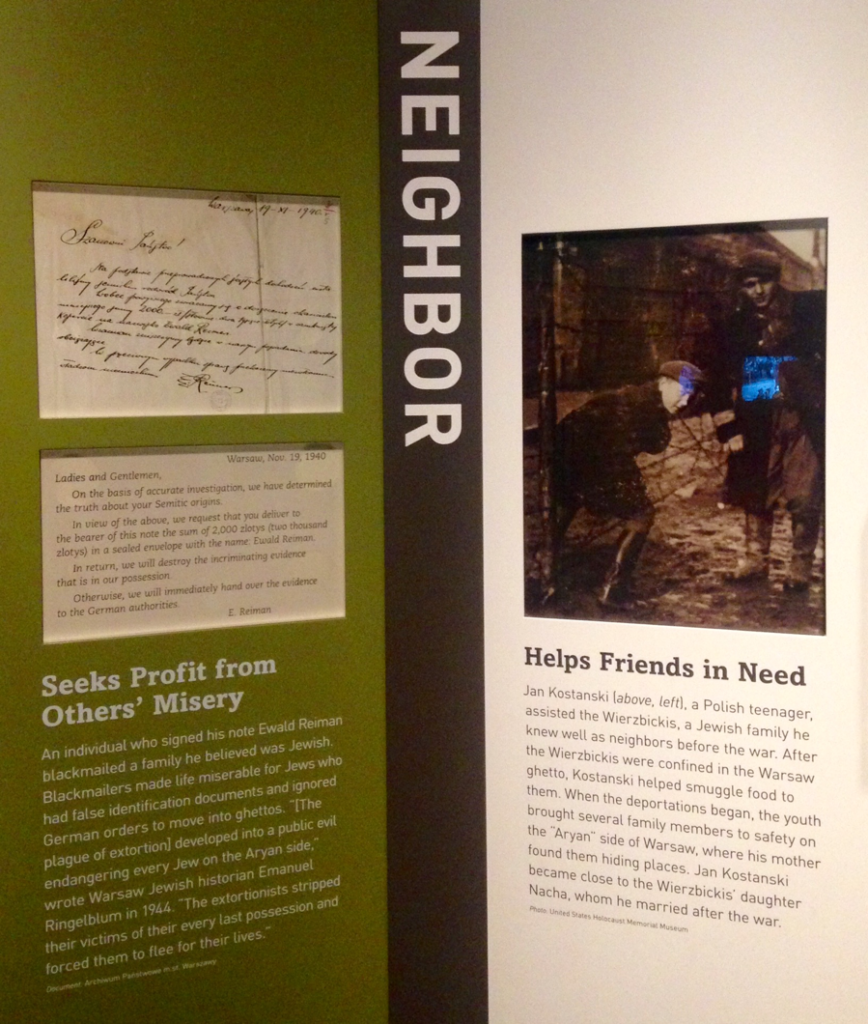

Source: I took this picture at the 2017 exhibit “Some Were Neighbors” at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

In my thirty-fifth year, my mind has been preoccupied with this simple but powerful idea: How we see others produces the society we see.

When we see others as cheap, foreign, and/or enemies, we produce a society of indifference, suspicion, and hatred. Patterns of poverty, conflict, and violence become inevitable. Bodies get dragged through the streets.

But when we see others as valuable, related, and neighbors, we produce a society where care, trust, and love are possible. Patterns of growth, cooperation, and peace become tangible.

How we see others is the fundamental issue for our future.

This applies from the individual to the national to the global levels. Our seeing shapes our attitudes, opinions, speech, and behavior. And these condense into what we call culture, economy, politics, and history.

If we see others as neighbors, we will treat them with kindness, respect, and care. If we see others as objects, strangers, or enemies, we will easily treat them with disregard, hardness, and abuse.

This raises a question that has also preoccupied my mind this year. How does our vision of others change?

In Jesus’s gripping story of the Good Samaritan, the priest “saw” the suffering man. But he did nothing (Luke 10:31). Another religious leader “saw” the suffering man. But he also did nothing (Luke 10:32). Jesus highlights their barren vision. Then a despised Samaritan “saw” the suffering man, and he “had compassion on him.” So he did something (Luke 10:33).

Three men “saw.” But only one saw the other as a neighbor, which catalyzed compassion. And so only one acted.

What made the difference in the Samaritan’s vision? Was it his experiences of being ignored or excluded as a minority? Was it his memories of pain and his desire not to abandon someone else to this agony? Was it a teaching in his heretical religion that inspired him to love across boundaries? Jesus doesn’t tell us.

Jesus simply tells us that three men “saw” the man left for dead. But only one saw him as a “neighbor” with “compassion.” And so only one – the ethnic, religious, and political enemy – acted with life-saving love.

How we see others produces the society we see, whether one that leaves half-dead bodies on the roadside or one that embraces and heals them.

And this leads me to my question: How can our vision of others change?

I dream of a society where others are seen as neighbors. This won’t magically solve all our problems. Neighbors can spread rumors, steal things, and abuse the vulnerable. None of us is innocent, and our life together is complicated. But neighbors typically treat one another with decency, respect, and care, and they find ways to resolve differences and wrongdoings without destroying one another to serve the common good.

Neighbor-vision that becomes neighbor-love is my passion going into year 36. It’s the foundation for a society in which human life is valued and shared flourishing becomes possible. I’m grateful for a new year of life with and for others across religion, color, ethnicity, language, money, health, age, politics, and the other identity markers that would divide us.

How we see others produces the society we see. How can our vision shift to see others – even strangers and enemies – as neighbors?