Dear friends,

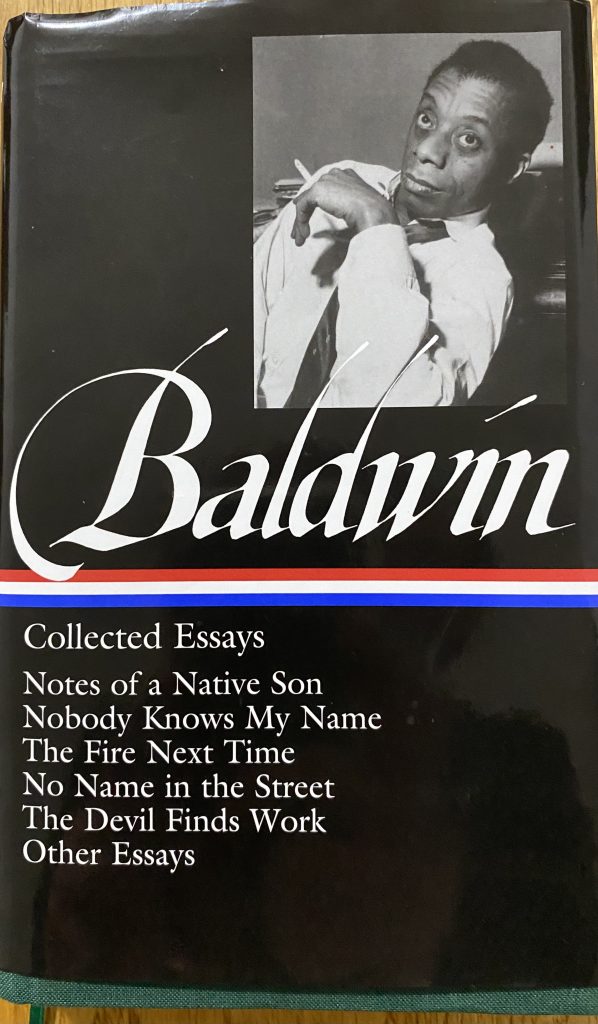

I consider James Baldwin (1924-1987) the greatest American writer that I have ever read. I’m tempted to say that Baldwin is simply the greatest writer that I have ever read. Albert Camus wrote with a stunning lyricism and honesty. But I think Baldwin surpasses Camus in both style and substance. (All of the quotations in this essay refer to Baldwin’s Collected Essays [New York: Library of America, 1998].)

I consider James Baldwin (1924-1987) the greatest American writer that I have ever read. I’m tempted to say that Baldwin is simply the greatest writer that I have ever read. Albert Camus wrote with a stunning lyricism and honesty. But I think Baldwin surpasses Camus in both style and substance. (All of the quotations in this essay refer to Baldwin’s Collected Essays [New York: Library of America, 1998].)

I would summarize Baldwin’s blazing ethical vision like this: If Patrick Henry declared, “Give me liberty or give me death!” James Baldwin would answer, “Give me truth or give me death!”

Baldwin’s Love of Truth

This is because Baldwin believed that real liberty is impossible without truth, and America was built on a lie. As such, America remains unfree and trapped in a captivating hypocrisy, even as it pridefully boasts of liberty.

To be free, we must face the truth, as all great thinkers have insisted from Socrates to Jesus to Hannah Arendt and beyond. In fact, “liberty” without truth can only lead to dehumanization, slavery, and death. As Baldwin demonstrates so poignantly, this is what we’ve seen in America from the bloody beginning.

For Baldwin liberating truth is the work of love:

“That’s one’s legacy, that’s all there is: and now only that work which is love and that love which is work will allow one to come anywhere near obeying the dictum laid down by the great Ray Charles, and – tell the truth…

People who cling to their delusions find it difficult, if not impossible, to learn anything worth learning: a people under the necessity of creating themselves must examine everything, and soak up learning the way the roots of a tree soak up water. A people still held in bondage must believe that Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make ye free.” (426, 432)

In short, then, truth is the core of James Baldwin’s ethical vision. He wrote, “I prefer to believe the day is coming when we will tell the truth about it — and ourselves. On that day, and not before that day, we can call ourselves free men” (621; see 179).

This core unlocks and unifies the utterly essential themes in Baldwin’s fiercely consistent but relentlessly original writing. I see the following as the five pillar convictions of his colorful ethical vision.

1. History: If we cannot honestly face the past, we remain prisoners of it and jailers of our present and future. The only way forward is back.

Baldwin calls us to radical self-examination and insists with Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living” (135, 391). Said differently, “we have to look grim facts in the face because if we don’t, we can never hope to change them” (216).

This is why Baldwin, despite his mesmerizing lyricism, is so difficult to read: he is unrelentingly honest about the evils of our past and thus the crimes of our present.

Baldwin insists, “it is precisely at the point that when you begin to develop a conscience, you must find yourself at war with your society. It is your responsibility to change society if you think of yourself as an educated person” (685; see 678). This, again, flowed out of Baldwin’s commitment to love: “the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself, and with that revelation, make freedom real” (672).

Later he wrote,

“To do your first works over means to re-examine everything. Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it. Sing or shout or testify or keep it to yourself: but know whence you came. This is precisely what the generality of white Americans can’t afford to do.” (841)

Or said differently,

“Neither whites nor blacks, for excellent reasons of their own, have the faintest desire to look back; but I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent and further, the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly…

We cannot escape our origins, however hard we try, those origins which contain the key – could we but find it – to all that we later become… It is a sentimental error to believe that the past is dead…

People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them… People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster…

The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.” (7, 21, 22, 119, 129, 723; see 208, 495, 602, 773)

This is Baldwin’s clarion call. We must confront “this long history of moral evasion” if we want to be truly free, for “freedom is the fire which burns away illusion” (183, 208). Baldwin didn’t see this as an intellectual debate but a moral emergency: “This perpetual justification [of our crimes] empties the heart of all human feelings. The emptier our hearts become, the greater will be our crimes” (178).

2. Critique: When we honestly face the past, we discover that America and Western civilization were founded on a lie.

For Baldwin, the lie at the heart of America is that “all men are created equal.“

In reality, America has proven again and again — through our founding genocide of Native peoples, enslavement of African peoples, segregation of African Americans, and ongoing marginalization of minorities today — that being “White” is the real, if denied, standard of human value in America. Indeed, Baldwin called “the idea of white supremacy…the very warp and woof of the heritage of the West” – “the most successful conspiracy in the history of the world” (126, 425). Surveying American history, Baldwin testifies, “the relevant truth is that the country was settled by a desperate, divided, and rapacious horde of people who were determined to forget their pasts” (693).

As we reckon with these rugged claims, we need to hear Baldwin’s voice and see through his eyes, remembering his own story.

Baldwin’s grandmother was born a slave (63). He himself grew up as a poor Black boy who made ends meet as a shoe-shiner in New York City’s streets where he was routinely beaten by the police. He was repeatedly called “ugly” and sexually abused. At home, he was badly beaten by his stepfather. Despite his astonishing gifts, he wasn’t able to go to college, worked in a factory, and was all-but abandoned for dead. Several times he experienced being kicked out of “White-only” establishments and found that Nazi prisoners of war were treated better than Black members of the American Army in which Baldwin served (70, 318).

Recollecting on this pain, Baldwin writes with touching intimacy:

“Only the Lord saw the midnight tears, only He was present when one of his children, moaning and wringing hands, paced up and down the room. When one slapped one’s child in anger, the recoil in the heart reverberated through heaven and became part of the pain of the universe.” (78)

Out of this painful experience, Baldwin testifies,

“Negro boys and girls [are] growing up and facing, individually and alone, the unendurable frustration of being always, everywhere, inferior… I can conceive of no Negro native to this country who has not, by the age of puberty, been irreparably scarred by the condition of his life… the wonder is not that so many are ruined but that so many survive…

That hundreds of thousands of white people are living, in effect, no better than the ‘n*ggers’ is not a fact to be regarded with complacency. The social and moral bankruptcy suggested by this fact is of the bitterest, most terrifying kind…

The brutality with which Negroes are treated in this country simply cannot be overstated, however unwilling white men may be to hear it… The administration of justice in this country is a wicked farce… the history of this country is genocidal.” (53; 173, 326, 445, 742, 804)

Of course, this is not how majority Americans see ourselves and our society: “no other country has ever made so successful and glamorous a romance out of genocide and slavery” (815). An American himself, Baldwin understood this and wrote, “Americans, unhappily, have the most remarkable ability to alchemize all bitter truths into an innocuous but piquant confection and to transform their moral contradictions, or public discussions of such contradictions, into a proud decoration” (24).

But Baldwin was blunt: he called this decoration “about as helpful as make-up to a leper” (42) and named it “our disrespect for the pain of others” (173). Despite public pressure, Baldwin refused to accept what he called “the grip of a weird nostalgia” (270):

“All of the Western nations have been caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism; this means that their history has no moral justification, and that the West has no moral authority…

[F]or millions of people, this history has been nothing but an intolerable yoke, a stinking prison, a shrieking grave… for millions of people, life itself depends on the speediest possible demolition of this history, even if this means the leveling, or the destruction of its heirs…

These people are not to be taken seriously when they speak of the ‘sanctity’ of human life, or the ‘conscience’ of the civilized world… The Western party is over, and the white man’s sun has set. Period…

The American soil is full of the corpses of my ancestors, through 400 years and at least three wars… It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one-ninth of its population is beneath them.” (404, 381, 489, 475, 716, 718; see 468)

Baldwin called this reality “the American torment” and “the spiritual famine of American life.” He insisted, “there is not, now, a single American institution which is not racist… This idea [of White supremacy] comes from the architects of the state” (834, 827, 839, 841).

But Baldwin went further in his critique. As a son of a preacher and himself once a preacher – “I was practically born in the church” – he rightly indicts American Christianity for harboring and perpetuating this lie of White supremacy (224, 499). He called this “the schizophrenia in the mind of Christendom” which made it “morally bankrupt and politically unstable” (314, 316). Reflecting on his time in the church, he wrote, “They take Jesus with them into the marketplace where He is used as proof of their acumen and as their Real Estate Broker, now, and as it were, forever” (840). In short,

“The Christian world has been misled by its own rhetoric and narcoticized by its own power… The people who call themselves ‘born again’ today have simply become members of the richest, most exclusive private club in the world, a club that the man from Galilee could not possibly hope — or wish — to enter.” (744, 784)

To this, Baldwin fiercely responded like Jesus in the Temple turning over our religious tables:

“If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him…

God is, after all, not anybody’s toy. To be with God is really to be involved with some enormous, overwhelming desire, and joy, and power which you cannot control, which controls you.” (314, 220)

At the World Council of Churches, he continued, “The destruction of the Christian Church as it is presently constituted may not only be desirable but necessary” (751). Dietrich Bonhoeffer said something strikingly similar soon before he was executed by the Nazis. Of course, Hitler’s Nazi regime was largely supported by self-professed German Christians.

Even so, Baldwin boldly critiqued the Black community too — for believing White lies and devaluing themselves to “make it” in White America. “The American image of the Negro lives also in the Negro’s heart,” he observed (29).

Baldwin sums up his double-edged critique like this:

“[P]art of the price of the black ticket is involved — fatally — with the dream of becoming white [superior]. This is not possible, partly because white people are not white [superior]: part of the price of the white ticket is to delude themselves into believing that they are [white]… America is not, and never can be, white [superior]… The people who think of themselves as White have the choice of becoming human or irrelevant.” (835-836, 812)

According to Baldwin, the secret at the heart of White supremacy is this: White power needs the Black person to be inferior, not because the White person is superior, but because he is insecure about his own worth and terrified of facing this vulnerability. And so diminishing another group of people makes this self-confrontation unnecessary, because, so the lie goes, making others less promises to make “us” more. Baldwin observed, “Men have an enormous need to debase other men” (392).

Said again, White supremacy became necessary in America not because of White superiority but because of a suppressed White insecurity. With searing but tender insight, Baldwin writes,

“I imagine that one of the reasons why people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with the pain… In a way, the Negro tells us where the bottom rung is: because he is there, and where he is, beneath us, we know where the limits are and how far we must not fall…

I think if one examines the myths which have proliferated in this country concerning the Negro, one discovers beneath these myths a kind of sleeping terror of some condition which we refuse to imagine. In a way, if the Negro were not here, we might be forced to deal within ourselves and our own personalities, with all those vices, all those conundrums, and all those mysteries with which we have invested the Negro race…

[W]hat they do and cause you to endure does not testify to your inferiority but their inhumanity and fear… When the prisoner is free, the jailer faces the void of himself.” (75, 219, 293, 563; see 682)

It’s crucial to understand that Baldwin’s uncensored critique is not meant to tear down but to build up. Again, his passion is truth, and he believes that truth is the foundation of freedom. So Baldwin sums up the constructive spirit of his critique like this:

“I love America more than any country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually… To accept one’s past – one’s history – is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought…

If I were still in the pulpit, which some people (and they might be right) claim I never left, I would counsel my countrymen to the self-confrontation of prayer, the cleansing breaking of the heart which precedes atonement.” (9, 333, 839).

I find this ethical vision extremely powerful: love leads to critique, and the goal of loving critique is “the self-confrontation of prayer, the cleansing breaking of the heart.” For Baldwin, “cleansing” and “breaking of the heart” are inseparable, and they come together and alive in the honest openness of prayer.

3. Equality: All humans are created equal.

Baldwin writes with smoldering incisiveness; there’s a rage – “the rage of the disesteemed,” “a humane and honest rage” – burning in his words when he confronts America’s addiction to lying and White supremacy (121, 585). But there’s a reason for this fire, and with Baldwin, it always cleanses rather than consuming. With incredible compassion, Baldwin writes,

“I didn’t meet any one in that [White] world who didn’t suffer from the very same affliction that all people I had fled from sufffered from and that was that they didn’t know who they were. They wanted to be something that they were not. And very shortly I didn’t know who I was, either. I could not be certain whether I was really rich or really poor, really black or really white, really male or really female, really talented or a fraud, really strong or merely stubborn. In short, I had become an American… The great problem is how to be – in the best sense of that kaleidoscopic word – a man.” (227, 232)

In his quest to be fully human, Baldwin’s unrelenting message from start to finish is that all human beings are fundamentally equal in value simply because we are human and children of God (752). Every single life is precious — unrepeatable and irreplaceable. With elegant simplicity, Baldwin writes, “Every human being is an unprecedented miracle” (357).

This is the pulsing heart behind all of Baldwin’s writing. The beauty of Baldwin’s love for people — especially the most scorned, debased, and abused — is breathtaking and fierce (431). With warmth, he states, “I love to talk to people, all kinds of people, and almost everyone, as I hope we still know, loves a man who loves to listen” (140). With modesty, he explains, “Negroes want to be treated like [people]” (177).

Perhaps the most moving moments of Baldwin’s work are when he writes about learning to love himself as an equally precious person – “dear to the sight of God” (750). Baldwin confesses that his father “knew that he was black but did not know that he was beautiful… he was defeated long before he died because, at the bottom of his heart, he really believed what white people said about him” (64, 291).

His father’s tormented sense of inferiority and Baldwin’s experience of poverty, sexual abuse, domestic violence, and racial humiliation haunted him and degraded his sense of worth. He confesses later, “It took many years of vomiting up the filth I’d been taught about myself, and half-believed, before I was able to walk on the earth as though I had a right to be here” (636).

Out of this painful autobiography, Baldwin was able to confess,

“To be liberated from the stigma of blackness by embracing it is to cease, forever, one’s interior agreement and collaboration with the authors of one’s degradation… I’m black and I’m proud.” (471-472)

This declaration of Black pride was not a reflection of any “reverse racism.” In fact, Baldwin directly condemns this, calling Black Americans to oppose “any attempt to do to others what has been done to them” (334). Baldwin clarified,

“I am proud of [Black] people not because of their color but because of their intelligence and their spiritual force and their beauty… All racist positions baffle and appall me. None of us are that different from one another, neither that much better nor that much worse.” (344, 747).

Baldwin’s declaration, then, of Black pride was a healing rejection of “the poison of self-hatred” that lies at the heart of all racism: that some people are inherently ugly and should to be ashamed to live in their own God-colored skin (185). Baldwin breaks out of this dungeon and celebrates, “I’m black and I’m proud.” He believed that when we can all learn to accept and love ourselves, racism becomes unnecessary, because we no longer need someone to be lower than ourselves (299-300). (Baldwin sees White supremacy essentially as an infantile and distorted attempt at “self-love” [452].)

Baldwin didn’t do this work of healing and self-love alone. He said, “No child can do it alone” (794). The artist Beauford Delaney enabled the young Baldwin to do this inner work with his love and mentorship. Looking back, Baldwin writes of Beauford,

“Beauford was the first walking, living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist… He became for me an example of courage and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow…

I learned something about myself from these irredeemable horrors: something which I might not have learned had I not been forced to know that I was valued. I repeat that Beauford never gave me any lectures, but he didn’t have to — he expected me to accept and respect the value placed on me.” (832)

What an extraordinary experience of love and insight into human healing: a true mentor is someone who “forces” you to recognize your own value and who expects you to accept and respect your own value as a unique person.

Baldwin strove to affirm this same value in others, especially struggling Black youth like himself. In a moving letter to his young nephew, Baldwin wrote, “you must survive because we love you… The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love” (293).

This was Baldwin’s manifesto:

“Our humanity is our burden, our life; we need not battle for it; we need only to do what is infinitely more difficult – that is, to accept it.” (18)

4. Shared Liberation: “We cannot be free until they are free” — that is, until we are all free.

The astonishing thing about James Baldwin is that, despite all his shattering trauma, he actually loved White people just as much as he loved Black people. He said, “We cannot be free until they are free” (295).

When confronted about this by Elijah Mohammed, the Black nationalist leader of the Nation of Islam, Baldwin wryly responded, “I love a few people and they love me and some of them are white, and isn’t love more important than color?” (310) He expounded later,

“[Love] began to pry open for me the trap of color, for people do not fall in love according to their color… This means that one must accept one’s nakedness. And nakedness has no color: this can come as news only to those who have never covered, or been covered by, another naked human being.

Because you love one human being, you see everyone else very differently than you saw them before – perhaps I only mean to say that you begin to see – and you are both stronger and more vulnerable, both free and bound. Free, paradoxically, because, now, you have a home – your lover’s arms. And bound: to that mystery, precisely, a bondage which liberates you into something of the glory and suffering of the world.” (366; see 795)

As the husband of an Ethiopian woman in our “interracial” marriage, this passage is extremely personal and powerful to me. Against currents in both White and Black culture, Baldwin affirmed our “universal humanity” and rooted it in the loving embrace of our naked bodies: “We are all each other’s flesh and blood… there is one race and we are all part of it” (194, 501, 578; see 828).

Refreshingly, Baldwin’s insistence on liberating truthfulness started with himself. Baldwin refused to scapegoat others – “The suffering of the scapegoat has resulted in seas of blood, and yet not one sinner has been saved, or changed, by this despairing ritual” (386). And thus he wrote, “the moral of the story (and the hope of the world) lives in what one demands, not of others, but of oneself” (358). Said more sharply, “truth is a two-edged sword – and if one is not willing to be pierced by that sword, even to the extreme of dying on it, then all of one’s intellectual activity is a masturbatory delusion and a wicked and dangerous fraud” (371).

With rare integrity, Baldwin was willing to be pierced by his own sword and resisted hating even those people who hurt him. After getting thrown out of a White-only diner, Baldwin wrote,

“My life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart… One must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair… I knew the tension in me between love and power, between pain and rage, and the curious, the grinding way I remained extended between those poles – perpetually attempting to choose the better than the worse.” (72, 84, 321)

Cleary, this choice – “this fight in the heart” – against hate wasn’t easy for Baldwin. It required painstaking spiritual practice. Baldwin called this

“an act of faith, an ability to see, beneath the cruelty and hysteria and apathy of white people, their bafflement and pain and essential decency. This is superbly difficult. It demands a perpetually cultivated spiritual resilience.” (182)

This is Baldwin’s beauty: he writes a blistering sentence that ends in an affirmation of his oppressor’s essential decency. And this is what Baldwin meant when he said,

“Love is battle, love is a war, love is growing up… Whether I like it or not, or whether you like it or not, we are bound together forever. We are part of each other… People who cannot suffer can never grow up.” (220-221, 343; see 321)

This moral courage to confront his own temptation to hate and then to practice mature love produced in Baldwin some of his profoundest insights:

“Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated.” (84)

“It is a terrible, an inexorable, law that one cannot deny the humanity of another without diminishing his own: in the face of one’s victim, one sees oneself.” (179)

“To encounter oneself means to encounter the other: and this is love. If I know that my soul trembles, and I know that yours does too; and, if I can respect this, both of us can live. Neither of us, truly, can live without the other.” (571)

“[I]t is not possible to banish or falsify any human need without ourselves undergoing falsification and loss. And what of murder? A human characteristic, surely. But the question must be put another way: is it possible not to embrace him? For he is in us and of us. We may not be free until we understand him.” (596)

“People who treat other people as less than human must not be surprised when the bread they have cast on the waters comes floating back to them, poisoned.” (472)

“That image one is compelled to hold of another person – in order, as I have said, to retain one’s image of oneself – may become that person’s trial, his death. It may or may not become his prison; but it inevitably becomes one’s own… it is simply not possible for one person to define another. Those who try soon find themselves trapped in their own definitions.” (620)

“Most people are not able to look on each other as human beings, and, in spite of everything, to treat each other that way. Until this happens, freedom is only an empty word.” (677; see 755)

Baldwin captured this utterly essential flow of insight in a single, luminous sentence:

“Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” (341)

And so Baldwin, choosing love, doesn’t simply write for Black liberation; he writes for White liberation too. Against the proliferation of polarization, he wanted to “make real and fruitful again that vanished common ground” (151).

Baldwin insightfully understood that “that vanished common ground” could only be realized when White people face our lies and violence. As such, Black liberation is only half of the American problem and half of Baldwin’s passion: “Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves: the loss of our own identity is the price we pay for our annulment of his” (20).

Notice how Baldwin, a Black man writing for a largely White audience, tenderly and intrepidly writes of “our dehumanization” and “the price we pay” (see 364, 509). In his very language, he rejects the us versus them mentality that divides us. For Baldwin, advocating for “Black pride” is always in service of this larger, universal liberation rooted in his desire for all people to flourish as equals. Thus he wrote, “what we really have to do is to create a country in which there are no minorities – for the first time in the history of the world” (221).

This was a man who loved his neighbors in all their colors and who believed in our shared flourishing. For Baldwin, the means and end are always the same: shared liberation – or, simply, love. This is why Baldwin’s uncensored critiques of White America never slipped into othering insults and humiliation.

He writes, “I would like us to do something unprecedented: to create ourselves without finding it necessary to create an enemy” (“Black Power and Anti-Semitism,” 251). Said more personally,

“The people I love…cannot be described as black or white; they are, like life itself, thank God, many many colors.” (839)

5. Hope: New beginnings are possible when we face our bitter truths and tell better stories.

Baldwin had a ruggedly realistic view of human nature. We run from the truth, cling to our lies, and rigidly resist change — even when we promise to change. He wrote,

“What men imagine they are doing and what they are doing in fact are rarely the same thing… The gulf between our dream and the realities we live with is something we do not understand and do not want to admit… it is one of the major American ambitions to shun this metamorphosis… the future is like heaven – everyone exalts it but not one wants to go there now… it has always seemed easier to murder than to change.” (163, 593, 597, 188, 698; see 671, 775)

The reason is simple: change is terrifying. Again with uncommon empathy, Baldwin writes, “Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety” (209). And so we see that Baldwin’s anthropology is actually quite gentle and generous: he doesn’t believe that we’re all terrible monsters; instead, he thinks we’re much more like frightened children (215, 751, 771).

But Baldwin never surrendered to pessimism. He writes,

“I think I know how many times one has to start again, and how often one feels that one cannot start again. And yet, on pain of death, once can never remain where one is. The light. The light. One will perish without the light…

This is why you must say Yes to life and embrace it wherever it is found — and it is found in terrible places; nevertheless, there it is: and if the father can say, ‘Yes, Lord,’ the child can learn to say that most difficult of words, ‘Amen.’” (705)

Courageously saying Amen, Baldwin believed new beginnings are actually possible, starting right in our place of pain. With startling sobriety, he wrote, “Life would scarcely be bearable if this hope did not exist” (126; see 196 and 374). Surveying the mountainous reality of human failure, Baldwin testifies,

“We look upon this experience with shame, but it is out of what has been our greatest shame that we may be able to create one day our greatest opportunity… the way to begin is by taking a hard look at oneself.” (605, 613)

This takes us back to the beginning – to Baldwin’s passion for truth. For Baldwin, these new beginnings aren’t the stuff of mass conversions or magical quick fixes (840). New beginning is the hard work of doggedly telling the truth about ourselves and insisting that a new story is possible for all of us.

And so Baldwin writes and writes and writes: “To tell his story is to begin to liberate us…” (34). He is desperate for us to face the truth so we can be set free to live into a new story. In this story, we rediscover human equality and shared liberation as honest, ordinary people in a semi-decent society.

Baldwin concludes with our mandate:

“We made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over.” (230; see 657)

The Moral Revolution We Need Today

To my mind, these are the five pillars of Baldwin’s ethical vision.

What holds them together is Baldwin’s core conviction, which was Jesus’s core conviction: “You shall know the truth, and truth shall set you free” (John 8:32).

When we love the truth, we can (1) face our history, (2) critique our failures, (3) rediscover human equality, (4) struggle for a shared liberation, and (5) experience new beginning. As he wrote, “Confrontation and acceptance is all that can save another human being… Love is the only money” (523, 566).

I believe Baldwin’s five-fold ethical vision is worthy of our life-long meditation and transformation. These pillars are the blazing lights of a mind on fire that can point us backward and so forward into our future. This is what Jesus called metanoia or spiritual revolution.

I conclude with gratitude for this beautiful man.

Thank you, Jimmy Baldwin! You once wrote, “I want to be an honest man and a good writer” (9). You were both, and you have my deep respect and admiration. I will always be your student in this vocation.

You also once wrote, “The revolution which was begun two thousand years ago by a disreputable Hebrew criminal may now have to be begun again by people equally disreputable and equally improbable” (750). I, among the disreputable and improbable, embrace this as my life’s work and secretly dedicate my new book Flourishing on the Edge of Faith to you.

“Love is the only money.”

PS: Dear teachers and professors, I was home-schooled, attended a small community college, graduated from a rigorous Christian liberal arts college (Wheaton) in theology and philosophy, and got my MA and PhD from an elite global university (UChicago) in religious and political ethics. But James Baldwin was never assigned in any of my classes. This is baffling to me and indicates the continuing racial bias in our education. Please give your students the precious gift of reading and learning from this brilliant, beautiful human being!