Dear friends,

Happy New Year and welcome to 2025!

We’re not only heading into a new year. We’re also entering the second quarter of the 21st century and a volatile cultural moment.

Amidst many joys, the signs of our times are troubling: we see rising violence and authoritarianism around the world, including here in the United States. According to PRRI’s “2023 American Values Survey,” more than one in three Americans (38%) believe that the country is so badly off track that they would support an authoritarian leader to try to fix it. More than one in three white Evangelicals (37%) agree, and almost half of Republicans (48%) agree. Almost one in four Americans (23%) believe violence may be necessary to save the country, and almost one in three white Evangelicals (31%) agree.

As Bob Dylan sang in 1963, “The times they are a-changin’.”

At the start of this new year and quarter century, I want to introduce you to the ethics of Alexei Navalny (1976-2024). Navalny was a dissident lawyer, organizer, and politician in Vladimir Putin’s Russia. He has much to teach us about moral responsibility, prophetic leadership, and everyday humanness in the face of authoritarianism.

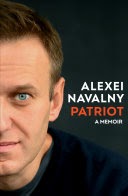

This essay is signficantly longer than my typical offerings; I highlight the passages below that are especially inspiring to me if you don’t have time to read this full essay. In it, I’ll briefly summarize some of Navalny’s core work and then distill ten lessons that I’ve learned from his powerful, posthumously published memoir Patriot (New York, NY: Knopf, 2024). All of the page numbers below refer to this book; I also encourage you to watch the powerful 2022 documentary Navalny.

Here at the beginning of our new year, I hope you’re inspired to embrace your own moral agency as you learn more about Navalny’s courageous life.

How to Defy Dictators: The Ethics of Alexei Navalny

In 2011, after graduating from university and beginning to practice law, Alexei Navalny founded the Anti-Corruption Foundation (ACF). ACF’s mission was to expose the systemic injustice and “rampant lawlessness” in Russian society (425). Navalny wanted to dismantle “the monster of dictatorship and its constant companion, war” (458). As he did this work, Navalny eventually became the most widely read blogger in Russia.

Navalny ran for mayor of Moscow in 2016 and for president against Putin in 2018. Navalny’s intention was to offer an alternative vision of moral leadership for his people. His dream was a “normal Russia” where people could live happier lives and not fear their government. Navalny called this “the Beautiful Russia of the Future” (273).

For these “crimes,” Navalny was repeatedly arrested. His public writings were deleted. He was banned from running for public office. Then in August 2020, he was brutally poisoned by Putin’s henchmen.

After surviving that attack and recovering in Germany, Navalny courageously chose to return to Russia in January 2021. Upon his arrival, he was arrested in the airport and imprisoned on bogus charges from a case that had been dismissed seven years before.

Navalny spent the next three years in prison. He observed, “what a repulsive, monstrous, perverted organization the Federal Penitentiary Service is” (394). Navalny himself was put in a notorious SHIZO or “punishment cell,” what he called “the customary place for the tormenting, torturing, and murdering of prisoners” – “a concrete black hole” (433, 451). His prison clothes were labeled SHIZO, and thus he was “branded an enemy” (433). He commented how commonly these prisoners were video-recorded being raped and tortured. These recordings were used to “relegate [prisoners] to the caste of ‘the degraded'” (434).

Finally, on February 16, 2024, Navalny was killed in solitary confinement in one of Putin’s atrocious gulags.

Navalny’s posthumously published memoir Patriot profoundly inspired me. In this essay, I explore ten lessons that I learned from it. I encourage you to read his book for yourself. But if you don’t have time to work through this 479-page tome, I hope these reflections offer insight into what energized this inspiring human. I see these ten lessons as crucial keys for defying dictators in our time of increasing authoritarianism.

With his signature dark humor, Navalny wrote, “I am sitting in a cell with nothing other than pen and paper, so ideal conditions for a writer” (131). Let’s dive in.

1. Tell the truth.

Like James Baldwin, Vaclav Havel, and many others before him, the beating heart of Alexei Navalny was the quest to tell the truth. He despised lies, refused to accept deception, and insisted on speaking truth to power. From prison, he wrote in a smuggled Instagram post, “A word of truth has tremendous power” (422).

This passion for truth began in Navalny’s childhood. He wrote, “The question most puzzling even to my ten-year-old self was why the authorities were lying like this when everybody around me knew the truth” (35). He came to see the authorities as “people not allowing you to say what is obviously true,” if not simply “members of a criminal gang” (43, 101). Thereafter, again and again, Navalny risked his life to live in the truth.

For Navalny, the core lie of Putin’s Russia is that ordinary people are “powerless and can’t change anything” (6). This oppressive imposition created a culture of normalized lying and seemingly omnipresent deception. Navalny called this “cliches, imbecility, and dishonesty” (74). Obvious realities were routinely denied in the most absurd but ferociously insistent ways.

The outcome of this master lie was that people couldn’t say what they thought or simply describe reality in an accurate manner without fearing for their safety. They became silent and secretive (469). Any critique was dismissed as “Western propaganda” and a “hidden agenda” to overthrow the government from neocolonial “enemies.” Navalny wrote, “Hypocrisy and lies inundated the whole country… [According to the government] the imagined idiot population is not yet ready for the truth… Putin never stops lying” (30, 31, 35).

Of course, the purpose of lies is to protect power. Navalny wrote, “Power equals money. Power equals opportunity. Power equals a comfortable life for you and your family, and everything you do while in power is aimed at retaining it” (123). Navalny saw this lie-protected power at the root of the mass poverty oppressing ordinary Russian people (275).

In the face of this lie-protected, power-hungry corruption, Navalny founded the Anti-Corruption Foundation in 2011. He defied Putin’s lie of powerlessness and claimed his own agency. After waiting with disappointment for an innovative politician to emerge, Navalny wrote, “one day I realized I could be that person myself” (188).

In the process, he observed, “I learned how much could be achieved without money and without the ‘protection’ of the Kremlin, indeed, in spite of the Kremlin… If you are not prepared to start with yourself and set an example, you will never achieve anything” (192, 224). Navalny courageously started with himself and set an example, and thus the Anti-Corruption Foundation (ACF) was established.

Regarding the ACF, Navalny wrote, “We called a thief a thief, corruption, corruption… Russia is built on corruption and everyone has a case” (6, 11). Navalny also told this truth with creativity. He wrote, “We simultaneously entertained and enraged our audience” by exposing the corruption of Russia’s most powerful elites, including Putin himself (7). The goal was to oppose the arbitrary impoverishing and killing of ordinary people and thus to steward “money for education and health care” (275).

In time, Navalny became the most famous blogger in Russia, seizing upon the emergence of social media. He named three keys to success on social media: write regularly, ask people to share your content, and interact with others on the platform (192-193). He wrote, “The best defense against lies is publicity. I had nothing to hide, and wanted everyone to see that the cases against me were politically motivated” (220).

Navalny was also willing to be brutally self-critical, to speak what he called “a dismal and disagreeable truth” (122). He wrote,

“Someday I believe it will all work out and everything will be fine, but we have to face the fact that from the early 1990s to the 2020s, the life of the nation has been wasted moronically, a time of degeneration and failing to keep up. There is good reason why people like me, and those five or ten years older, are called the cursed and lost generation… we should be honest, repudiating hypocrisy and any attempt to justify ourselves for our wasted years… they were not good times for me, and it drove me crazy when people told me they were.” (115, 116, 119)

This vocation of truth-telling motivated Navalny to return to Russia after he had been nearly poisoned to death and narrowly escaped to a German hospital in August 2020. At the airport upon his return to Russia in January 2021, he declared, “I am very happy to be back home and know I have truth on my side” (149). Moments later, he was arrested at passport control, never to be free again.

Navalny reflected, “Russians yearn for a normal life, aware that we have invented all our existing problems for ourselves. We can’t admit to being fools, though, so we look for something to boast about, where in fact there is nothing to be proud of” (41-42). Here Navalny talked about the power of nostalgia and nationalism, how politicians make us long for an imagined golden age in the past to cope with our feeling of insecurity in the present.

To this, Navalny hilariously wrote, “It is important for us to behave like human beings rather than goldfish, whose memory is famously said to be limited to the past three seconds… I have no wish to go back to the days of the USSR. A state incapable of producing enough milk for its citizens does not deserve my nostalgia” (50).

In one of the bogus court cases against him in 2014, Navalny summarized his view of life, truth, and moral leadership. He testified,

“Sadly the whole system of power in our country, and everything that’s happening, is based on endless lies… Why do you put up with these lies? Why do you just stare at the table? I’m sorry if I’m dragging you into a philosophical discussion, but life’s too short to simply stare down at the table… at some point we’ll realize that nothing we did had any meaning at all, so why did we just stare at the table and say nothing? The only moments in our lives that count for anything are those when we do the right thing, when we don’t have to look down at the table but can raise our heads and look each other in the eye. Nothing else matters.” (238-239)

Navalny’s commitment to looking up from the table and telling the truth was relentless. Even in the face of arrest, poisoning, and imprisonment, he insisted, “Maybe this is going to sound naive, and I know it’s become the norm to laugh ironically and sneer at these words, but I call on absolutely everyone not to live by lies. There is no other way. There can be no other solution in our country today” (242).

Navalny was convinced that truth is more powerful than lies. And thus he refused to submit to dishonesty and insisted upon a life of truth-telling in the face of dictatorship. He declared,

“Power is in the truth… Whoever has truth on their side will win… Just think for yourself how good life would be without this constant deceit, without all this lying. Being able not to lie is just amazing… It is very important not to be fearful of people who are seeking the truth… So what’s my first duty? That’s right, not to be intimidated and not to shut up.” (328-329, 446)

2. Don’t be afraid of anything.

Authoritarian leaders are afraid of people who seek to live in truth. Truth challenges the foundation of their corrupt power. Thus, authoritarian leaders will attempt to control, crush, and kill truth-tellers. Navalny observed, “The authorities… are afraid not [just] of honest people but of those who are not afraid of them. Or let me be more precise: those who may be afraid, but overcome their fear” (420; see 459). When the Anti-Corruption Foundation was labeled as an “extremist organization,” he wrote, “They’re scared of us” (388). He later commented, “When corruption is the very foundation of a regime, those who battle it are extremists” (399).

But Navalny testified that we shouldn’t be afraid of these “authorities” or their violence. When we live in the truth, we have nothing to fear. He wrote, “We must do what they fear – tell the truth, spread the truth. This is the most powerful weapon against this regime of liars, thieves, and hypocrites. Everyone has this weapon. So make use of it” (460).

When Navalny was arrested at the airport in 2021 and taken outside to a police car, he was astonishingly composed and clear-minded. He called out to the people gathered around, “Don’t be afraid of anything!” Navalny later reflected,

“That was an important moment, the kind when you feel at one with your supporters. They are thinking of you and want to show you they are with you. You are thinking about them, and that the regime needs this arrest to frighten them, and you do your utmost to help them not be afraid. You keep your back straight and shout, ‘Don’t be afraid of anything.’” (162)

Refreshingly, Navalny didn’t see himself as an unusually courageous person. He described himself as someone who had made “a conscious choice” based on his moral values. He wrote, “Nowadays I get asked in nearly every interview where I get my courage. I genuinely believe my work in the past twenty years has not called for bravery; it is more a matter of having made a conscious choice” (89).

Navalny later noted with his characteristic humor, “I firmly believe that all the best things on earth have been created by brave nerds… My heroes are those brave nerds who brought about a revolution and enabled the progress of all humankind” (183). Considering the alternative, he asked, “Why live your whole life in fear, even being robbed in the process, if everything can be arranged differently and most justly?” (421).

This brave nerdery was the heart of Navalny’s truth-telling politics. He wrote, “The gist of my political strategy is that I am not afraid of people and am open to dialogue with everyone. I can talk to the right, and they will listen to me. I can talk to the left, and they too will listen to me” (185). This political strategy was grounded in his humble sense of universal humanity: “I was just an ordinary person like the rest of them, except I was not afraid to get up on the stage” (197). He insightfully understood that his arrest really wasn’t about making him afraid but trying to make ordinary people feel afraid and thus submissive (460). To this, Navalny cried out, “Do not lose the will to resist” (460).

Navalny saw this fear-defying truth-telling as answering the call of ordinary Russians. He heard them saying, “We are ready to fight but need a leader, someone who is not afraid of the state and will not accept bribes” (213). Thus he chose to start with himself and set an example.

Like any of us, Navalny didn’t want to suffer. He wrote, “I have always tried to ignore the idea that I could be attacked, arrested, or even killed.” But he remained grounded in that “conscious choice” he had made. He wrote, “one day I simply made the decision not to be afraid. I weighed everything up, understood where I stand — and let it go” (271). I’m not sure I would have believed this decision was possible, but after my dad died in April 2024, I now understand Navalny’s experience and how possible it truly is for ordinary people.

Once again, Navalny clarified that he wasn’t a hero. Instead, he was energized by love and the moral integrity of his work. He wrote,

“I love what I do and think that I should keep doing it. I’m not crazy, nor am I irresponsible or fearless. It’s simply that deep down I know I have to do this, that this is my life’s work. There are people who believe in me… I’m a Russian citizen, I have certain rights, and I’m not prepared to live in fear. If I have to fight, then I’ll fight, because I know that I’m right and they’re wrong. Because I’m on the side of good and they’re on the side of evil… I realize these are very basic ideas, maybe even populist, but I believe in them, and that’s why I’m not afraid. I know I’m right.” (271-272)

When Navalny’s son Zakhar told his classmates, “My daddy is fighting against bad people for the future of our country,” Navalny called this “the greatest day of my life” (273). Unwilling “to live in fear,” he embraced his life’s work with prophetic courage and inspired his son.

In his prison diary, after being sentenced to 3.5 years in prison, Navalny wrote, “I’ve had the same frank conversation with myself a hundred times: Do I have any regrets, do I worry? Absolutely not. The belief that I am in the right, and the sense of being part of a great cause, outweighs all the worries by a million percent” (299). Near the end of his life, he noted, “The only thing we should fear is that we will surrender our homeland to be plundered by a gang of liars, thieves, and hypocrites” (421).

Thus, Navalny faced and transcended his fear to live in the truth.

3. Organize.

Navalny observed that many Russians were frustrated with the state of their society, but they weren’t doing anything practical about it. In response, Navalny wrote, “I was looking for allies, not just [social media] followers” (195). As Navalny experimented with publishing critical investigations of state corruption online and engaging in public debates, he wrote, “The main thing I learned…was how to get large numbers of people working with me… People are glad to volunteer their services” (209).

Navalny started mobilizing a volunteer base of web designers, lawyers, journalists, and others to defy Putin’s corrupt authoritarianism. Rather than depending on a few major donors, he asked thousands of people to give small amounts of money to sustain his work (211). This made it harder for Putin to strangle his efforts. In 2011, he founded the Anti-Corruption Foundation, a hybrid organization of lawyers, journalists, and activists (214).

With time, Navalny started investigating elite corruption and organizing protests around Russia. He wrote, “The most important thing we do is, then, to spread the story so millions hear about it” (214). The ACF started producing detailed documentaries about high-level corruption in Russia. Later in 2011, he was predictably arrested for the first time (217).

From prison, Navalny reflected, “The year 2012 set a pattern in my life, an endless vicious circle for many years to come: protest rally, arrest, protest rally, arrest. It was unpleasant, of course, but that was not going to stop me” (219). He had faced his fear and made his choice to live in the truth.

Navalny then went on to run for mayor of Moscow in 2016 and president of Russia in 2018, though his candidacy was banned. Even so, he established offices in over 80 cities across Russia. Navalny called this “a permanent working structure for the opposition, a new form, capable of bringing people out onto the streets in any city, to take part in elections, and to win them” (265, 470).

In short, Navalny didn’t simply tell the truth as a courageous individual; he organized. He gathered a volunteer base, mobilized them in a flexible organization, and spread a movement for democracy across Russia in the face of Putin’s authoritarianism.

4. Remember that you’re not alone.

Authoritarian power seeks to isolate truth-tellers and trap them in loneliness (295, 327). When we’re alone, we begin to feel insane — like we’re the ones who are wrong for raising our voice against injustice. But Navalny reminds us that we are not alone, and there are more people who hunger for freedom than those who oppress it.

From prison, Navalny confessed, “When you are behind bars, you really need something good to hold on to” (153). Again and again, Navalny names and celebrates the goodness that he held onto: the support he received from others.

The first time he was arrested in 2011, Navalny was encouraged knowing 100,000 Russians protested in Moscow against election fraud. He insisted there were more “honest people” in Russia than corrupt power-mongers. He wrote, “The Russian people are good; it’s our leaders who are appalling” (184).

When he was arrested upon his return to Russia in 2021, someone at the airport yelled, “Alexei, hold on. All Russia is with you!” (286) Navalny journaled in prison about how this stranger’s encouragement deeply moved him. He observed, “a prisoner’s most important task [is] driving away all thoughts of loneliness… there is no better weapon against injustice and lawlessness [than people’s support and solidarity]” (389).

Later, Navalny movingly recalled receiving a small notecard in prison and wrote that he wanted to go up to the camera in his cell and shout at his invisible guards, “See you, bastards, I am not alone!” (414). He said this note “left me feeling morally and physically better” (414). He kept it in his breast pocket and said it felt like it was “beating mighty wings” (415).

Navalny’s most sustaining companion was his courageous wife Yulia who relentlessly supported him. Yulia smiled and laughed with him through everything to the very end.

Chapter 9 of Patriot tells the story how Alexei met Yulia unexpectedly on a work trip in Turkey. After seeing her smile, he told himself, “This is the girl I will marry” (171). About Yulia, Navalny wrote, “There is such a thing as a ‘kindred soul.’ I’m sure there is one for everyone. When you meet your soulmate, you just know” (173).

Though often behind the scenes, Yulia was fully supportive of her husband’s work, and that “kindred soul” sustained him (225, 273). After over two years in prison, he wrote to her, “I have you, and no matter what happens, just thinking about that makes me very happy” (174). Describing movie cliches, Navalny wrote, “their partner, through their love and ceaseless devotion, brings their partner back to life. And, of course, that’s exactly how it was with us… love heals and brings you back to life. Yulia, you saved me” (23-24).

In prison, Navalny was often denied his right to have visitors, including Yulia. But the thousands of letters he received from his supporters helped sustain his spirit. He journaled, “Every second letter brought tears to my eyes just reading them. People are so good” (288). He said that his favorite letter simply said, “Alexei, I wish to inform you that I am very pleased with you” (305; 433) — a reminder of how essential positive affirmation is for us humans. I am reminded of God’s words to Jesus at the beginning of his public movement: “You are my beloved child; I’m very pleased with you” (Luke 3:22).

With the support of Yulia and his many penpals, Navalny wrote defiantly, “I know one thing for sure: that I am among the happiest 1 percent of people on the planet — those who absolutely adore their work… Our country deserves better” (273). In a smuggled Instagram post, he called people’s support “the most important thing someone in my situation needs” 321). He declared, “There are plenty of us, certainly more than corrupt judges, lying propagandists, and Kremlin crooks. I’m not going to surrender my country to them” (452).

To defy dictators, Navalny reminds us that we need to remember we are not alone. The support of others, whether the love of an intimate partner or the encouragement of strangers, can sustain us.

5. Endure suffering with spiritual discipline.

Navalny was subjected to the cruelest solitary confinement and deprivation in Russian prison. When he started challenging Putin’s power, he knew this is what he was getting himself into.

Before he was imprisoned in 2021, Navalny wrote, “That version of my future is grim, but it is the only one that is not shameful” (60). Looking back from prison, he added, “In one corner there would be Putin’s corrupt oligarchs and bureaucrats and in the other there would be me” (194). But having made his conscious choice not to be afraid and to tell the truth, Navalny decided this David-and-Goliath struggle was worth it.

Navalny endured this terrible suffering through his spiritual practice. To be clear, Navalny grew up as an atheist who thought his grandmother’s belief in God was silly. What converted him?

It was his daughter Dasha’s birth. Navalny wrote,

“I had never believed in God, but looking now at Dasha and how she was developing, I could not reconcile myself to the thought that this was only a matter of biology. That did not alter the fact that I’m still a big fan of science, but I decided at that moment that, on its own, evolution was not enough. There must be more. From a dyed-in-the-wool atheist, I gradually became a religious person.” (181)

Navalny repeatedly wrote about how easy it would be to vegetate in prison by watching television. He called TV “the scourge of prison…the godforsaken idiot glow-box” (395). But Navalny resisted this easier path and described three spiritual practices that sustained him amidst his suffering in Putin’s prisons.

First, Navalny practiced meditating on Jesus’ Beatitudes.

Navalny called this practice “a delight” and “my only entertainment” (409). The Beatitudes was Jesus’ spiritual manifesto about the way to humane happiness at the beginning of his movement. It started with Jesus’ declaration that “the poor in spirit” are promised “the kingdom of heaven” and concluded with the same promise for those who are persecuted for the sake of justice. (I unpack Jesus’ Beatitudinal Way in my book Blessed Are the Others.)

Navalny memorized Jesus’ Beatitudes and the Sermon on the Mount’s 111 verses in Russian, English, French, and Latin. Committed to memory, Jesus’s words would always be with him and could never be confiscated by his guards as “extremist content” (409). In Jesus’ teaching, Navalny found the spiritual power he needed to defy Putin’s dictatorship. Recalling his first encounter with these words of Jesus, Navalny wrote, “I almost fainted, and only with immense difficulty kept my teardrops from turning into torrents. I left the church dazed and walking on air. And no longer hungry” (411).

The moving testimony that Navalny gave about his Beatitudinal practice at one his prison trials is worth quoting at length:

“It’s not always easy for to do what this book [the Bible] says, but I try. And that’s why it’s easier for me than for many other people who do politics in Russia. Recently someone wrote to me. ‘Navalny,’ he says, why is everyone telling you to “stay strong,” “don’t give up,” “stick out,” and “grit your teeth”? What is it you’re having to put up with? Didn’t you say awhile back in an interview that you believe in God, and it says in the Bible, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be fulfilled.” Well, that’s great. You’ve got it made!’ And I thought, How about that! How well this person understands me. I’m not sure I’ve got it made exactly, but I’ve always accepted that particular precept as pretty much an instruction on how to act. That’s why I feel, while of course I’m not particularly enjoying my present situation, I feel no regret about having returned here and what I’m doing. Because everything I did was right. On the contrary, I feel, well, a certain satisfaction… I don’t [feel lonely], and let me explain why. Because those words — ‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness’ — seem exotic and a bit weird, but they actually express the most important political idea in Russia at this moment.” (326-327)

For Navalny, “the most important political idea” was that righteousness or justice is the way to true happiness. Rather than leaving us starved, the hunger for justice will ultimately be satisfied. Power doesn’t define reality. Truth does. And truth is on the side of justice. This radical trust nourished Navalny’s fearlessness and struggle for change. Navalny ended his courtroom speech by echoing Jesus’s promise in the Beatitudes: “Russia will be happy!” (330).

The final paragraphs of Navalny’s memoir return to this meditation on Jesus’ Beatitudes and Navalny’s trust in them. Again, they are worth quoting at length:

“[Spiritual practice] is doable only for believers but does not demand zealous, fervent prayer by the prison barracks window three times a day (a very common phenomenon in prisons). I have always thought, and said openly, that being a believer makes it easier to live your life and, to an an even greater extent, engage in opposition politics. Faith makes life simpler… ask yourself whether you are a Christian in your heart of hearts. It is not essential for you to believe some old guys in the desert once lived to be eight hundred years old or that the sea was literally parted in front of someone. But are you a disciple of the religion whose founder sacrificed himself for others, paying the price for their sins? Do you believe in the immortality of the soul and the rest of that cool stuff? If you can honestly answer yes, what is there left for you to worry about? … Don’t worry about the morrow, because the morrow is perfectly capable of taking care of itself. My job is to seek the Kingdom of God and his righteousness, and leave it to good old Jesus and the rest of his family to deal with everything else. They won’t let me down and will sort out all of my headaches. As they say in prison here: they will take my punches for me.” (479)

Those are the final words of Alexei Navalny, his last testament. In them, we hear the profound political implications of the resurrection, Jesus’ promise of life beyond death or “the immortality of the soul.” If God is able to give us a new life beyond death, then we have nothing to fear before we die. “Good old Jesus” will “take my punches for me.”

And so a godlike dictator like Putin is resized as the small, fearful human that he is who needn’t be feared or submitted to. The hungry will ultimately come home to a feast of justice in the resurrection. Like Jesus taught, they can trust that “the morrow is perfectly capable of taking care of itself” – even if that morrow means being murdered in an oppressor’s prison.

Second, Navalny practiced “prison Zen.”

While he courageously trusted his “morrow” to God’s faithful love, Navalny held no illusions about what that morrow might entail. He consciously, actively faced it and then accepted it.

Having received “an extremely long sentence,” Navalny decided to start practicing his “prison Zen” and did so for three years (464, 473). He acknowledged that his life would be so grim that it might drive people to “hang themselves or slash their wrists” (474). This is what the practice of prison Zen involved: “You invite yourself to imagine, as realistically as possible, the worst thing that could happen. And then, as I said, accept it (skipping the stages of denial, anger, and bargaining” (476). (Navalny is alluding to the five stages of grief that Elizabeth Kübler-Ross outlined in her book On Grief and Grieving.)

For Navalny, this exercise evoked many painful possibilities. He envisioned that he would spend the rest of his life in prison, that no one would say goodbye to him before he died, that he wouldn’t be able to attend his children’s birthday parties and graduations, that he wouldn’t be able to celebrate his wedding anniversaries with Yulia, that he would never meet his grandchildren, and that he wouldn’t be “the subject of any family stories” or present in any family photos (476).

Navalny acknowledged that his “prison Zen” was grueling. He wrote, “your cruel imagination will whisk you through your fears so swiftly that you will arrive at your ‘eyes filled with tears’ destination in next to no time” (476). But he refused to live in denial or trick himself with false optimism. He said the goal of this exercise was not to trigger “anger, hatred, fantasies of revenge, but to move instantly to acceptance” (476). It wasn’t a masochistic fantasy but an acknowledgement of reality, both in his own suffering and what other Russians were suffering. He wrote, “Right now, dead civilians are lying in the streets in Mariupol [Ukraine], their bodies gnawed at by dogs” (477).

I appreciate Navalny’s honesty. He wrote that when he started practicing his prison Zen, he had to stop and take a break. He was overcome with “an urge to start furiously smashing everything” and yelling “You bastards!” (476). But as he meditated on Jesus’s Beatitudinal Way in four different languages, he was able to do his prison Zen and accept his fate. In the penultimate page of his memoir before being killed in prison, he wrote,

“I am completely fine. Even ‘my’ jailer said in the course of a really annoying full strip search, ‘You don’t look to me to be all that upset.’ I am really okay. I am writing this not because I am willing myself to keep up a pretense of being carefree and blasé but because my prison Zen has kicked in.” (474)

The courage to defy authoritarianism isn’t sustained by false optimism. It requires looking directly into the face of suffering and accepting that suffering. This unflinching honesty is held in the trust of Jesus’ promise that dictators can do their very worst to us and Jesus will “take [our] punches for [us].” In a letter to Yulia, Navalny wrote, “Let’s just decide for ourselves that this [death in prison] is most likely what’s going to happen. Let’s accept it as the base scenario and arrange our lives on that basis. If things turn out better, that will be marvelous, but we won’t count on it or have ill-founded hopes” (478).

That is exactly how “things” turned out for Navalny and Yulia. Their decision to practice “prison Zen” sustained him to his death and Yulia still today.

Third, Navalny practiced vipassana.

This a Buddhist technique of conscious breathing that focuses on the flow of oxygen in and out of our nostrils. It is meant to make us aware of the constant, dynamic change that is taking place in our bodies as we breathe, starting simply in our noses. Once this is acknowledged and accepted in our nasal passages, it is then meant to extend to the whole body and become a total acceptance of our fragility as embodied creatures.

Refreshingly again, Navalny wrote that he was “highly skeptical” of “such spiritual practices” (440). But he was inspired by the historian Yuval Harari and found vipassana “a practical way to explore yourself, your brain, and the process of cognition” (441). In its simplest form, Navalny called this meditation “just a way of learning to control your thoughts” (441). He wrote that it was difficult, but it made his prison cell “less infuriatingly uncomfortable.” He learned to “plug in” to “a state of suspended animation” (442) and said, “my cell is basically vipassana” (437).

In short, then, Navalny was able to endure the terrible suffering of his truth-telling vocation in the face of authoritarianism through disciplined spiritual practice. For him, this practice took the form of daily meditation on Jesus’ Beatitudes with its unkillable hope, the prison Zen of accepting the worst-case scenario of his imprisonment, and centering his consciousness in the breath-work of vipassana. He added, “It would be absurd even to think of straining for a new life without sport and physical exercise every morning” (133).

6. Protest oppression with playfulness.

As serious as he was, Navalny’s spiritual practice was anything but sullen. He had an incredibly powerful capacity to remain cheerful in the face of evil.

Across the pages of Patriot, we witness how Navalny practiced playfulness as a form of protest. His book is laced with jokes and laughter. Navalny insisted, “[Putin is] not omnipotent” (6). With this conviction, he would take the absurdity, spite, and cruelty that was inflicted upon him and turn it into a cause for connection, laughter, and even joy. He called this playfulness “the wholesale desacralization of the regime” (55). When he was given a sheepskin coat in prison, he joked, “I am your new Santa Claus… But I am a special-regime Santa Claus, so only those who have behaved really badly get presents” (465).

In The Twilight of the Idols, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, “Maintaining cheerfulness in the midst of a gloomy affair, fraught with immeasurable responsibility, is no small feat; and yet what is needed more than cheerfulness?” Navalny wrote something similar in an Instagram post he got smuggled out of prison: “as long as you can see the funny side of things, it’s not too bad” (360).

When Navalny was arrested at the airport upon his return to Russia in 2021, he laughed in the presence of the police. This was his form of protesting the absurdity of their behavior. In an iconic picture of his arrest, he smiled and formed his hands into a heart.

Later in his prison diary, Navalny wrote about being taken into an interrogation room with a large mirror. He knew that people were sitting behind it observing him. He said that he was tempted to sneak along the wall and jump in front of the mirror to startle them. He wrote, “If there are dudes behind the mirror, they must be thinking, ‘This man is wrong in the head. He keeps writing things down and hooting with laughter’” (281).

Hooting with laughter, Navalny wrote in another smuggled Instagram post, “I’m commonly asked if I’m depressed. No, I’m not depressed. Prison, as we know, is in the mind. And when you really think about it, you’ll see that I’m not in prison. I’m on a journey into space” (321). Navalny then hilariously wrote about reimagining his prison cell as a spaceship on its way to “hugging your family and friends in a brave new world” (322).

With his defiant humor, Navalny refused to let his oppressors imprison his mind. In his diary, he frequently referred to his imprisonment as a galactic adventure thereafter (430, 443).. In the same spirit, he gave a mischievous speech at one of his court trials that he entitled “Russia Will Be Happy” (325).

In light of his “prison Zen,” Navalny’s choice to laugh in the face of injustice was obviously not an act of ignoring injustice; it was an act of exposing it. With Jesus’ promise that the hungry for justice will be fully filled, he came to see that injustice is ultimately unserious and absurd. It deserves to be ridiculed and laughed at – to be unmasked as the foolishness that it is. In one of his smuggled prison Instagram posts, he wrote, “life gives you wonderful moments when you can laugh and be happy” (389).

It seems that Navalny’s unbreakable spirit was rooted in his love for music. He wrote, “The crucial source of ideological sabotage that subverted me and turned me into a little dissident was music” (46). He especially enjoyed the culturally condemned Western rock music with its “punk philosophy” (114).

Throughout his work and writing, Navalny reminds us to protest oppression with playfulness – to laugh in the face of oppressors. With humorous snark, he jabbed in a smuggled post,

“I’ve been getting a lot of letters lately from the outside about depression, gloom, and apathy. Seriously? Come on, cheer up. If you’re alive and well and out there, you’re doing all right. Finish your pumpkin latte and go do something to bring Russia closer to freedom.” (448)

7. Embrace the mundane and cherish the simple things.

Much of Navalny’s prison diary is unextraordinary (356). He wrote about the food he was eating, his terrible back pain, and his sleep schedule. He recorded his seemingly meaningless interactions with other prisoners, his exercise routine, and the books he was reading. He often commented on the the absurdity of the prison rules, how he was repeatedly strip searched, and the rage this produced in him. Frankly, some of the pages in Patriot were repetitive and boring. At points, I was tempted to lose interest and thought to myself, “Where are the profound philosophical meditations on life’s ultimate issues?”

But with these writings, Navalny was consciously embracing the mundaneness of his everyday life in prison. For example, he reserved eating white bread for Sundays so they would become “a really special day of festivity” (307).

As a truth-teller and freedom-fighter, Navalny’s ultimate goal for Russia was a normal, happy life. He wasn’t seeking total revolution or utopian perfection. In the process of being a prisoner, he came to an even clearer perception of how precious the most basic gifts of being human truly are. He refused to take anything for granted, including the most simple.

Navalny wrote about how he loved watching beautiful snowflakes flutter through the prison’s barbed wire (313). He called receiving salt to put in his prison salads “bliss” (317). After Yulia was able to visit him in prison, he wrote in a smuggled Instagram post, “Appreciate the simple moments of life, my friends. They are very, very good, as you realize when you lose them” (401).

Here Navalny urged people to spend time with their spouses and parents and to cherish being able to do so “without bars and glass separating you” (402). He urged, “try conducting a mental experiment: imagine you have had that taken away, and you will instantly feel an urge to hug everyone” (402).

Navalny’s attention to his everyday life was an act of survival and dignity. He reminds us to embrace the mundaneness of our lives and to cherish the simple things, like being able to hug loved ones, even in the midst of a painful struggle against authoritarianism.

8. Stay affectionate.

Navalny signed-off many of his prison reflections and smuggled posts with words like “I love you all. Hugs to everyone” (422). He wrote, “Friends, my heart is full of gratitude and love for you” (390).

There is a sense of warmth and affection throughout Navalny’s writing, even when he wrote in a Siberian prison camp that was -25 degrees Fahrenheit. From there, he wrote with mirth, “Arctic hugs and polar greetings. Love you all” (467).

Navalny was honest about losing his temper and cursing out his prison guards. He confessed, “I have shown myself to be an insensitive person of low emotional intelligence” (370). It’s hilarious to read his confession that his Lenten fast of not “raising his voice” against his guards and “loving everyone” failed so quickly and miserably (373).

But as humiliating as it was, he strove to be a “meek little Christian, constantly apologizing to everyone and speaking in a kind, well-meaning tone of voice” (370). He urged his followers to “hug everyone at every opportunity you get” (402).

Much like Etty Hillesum in the face of the Holocaust, Navalny refused to be hardened by his experience. He remained tender, affectionate, human to the end. He urged us to do the same: “hug everyone at every opportunity you get.”

9. Respect democratic rights for all, even amidst fierce disagreement.

Navalny has been criticized for appearing at public events in Russia with hardcore nationalists and skinheads. Some have worried that Navalny’s appearances with these people revealed racist or even antidemocratic tendencies in his own worldview.

But Navalny addressed this criticism directly in Patriot. He wrote, “I decided that if I, with my democratic values, supported the right of free assembly, I needed to be consistent and support other people’s right to do the same” (185). He confessed that some of the people at these rallies were “repugnant” to him. But his commitment to democracy with its rights to freedom of speech and assembly required him to tolerate people with views he himself fiercely opposed. He wrote, “Such people should be defeated in elections” (454).

In a time when many people rally around “taking back” their cultures and countries, I find Navalny’s principled presence among people he disagreed with refreshing and challenging. He reminds us that authentic democracy cannot be “possessed”; it must be patiently participated in, even when this requires uncomfortable encounters and controversial associations.

Still, Navalny wrote with passionate conviction, “I am against the [Ukraine] war. You should say that too” (426).

10. Never give up: everything will be okay in the end.

“Never give up” is the drumbeat of Navalny’s life. He refused to conform or crumble to Putin’s oppressive power.

Yes, Navalny suffered terribly and practiced his “prison Zen” for three years until he was ultimately killed in prison. But Navalny remained invincibly convinced that truth overcomes lies, that goodness outlasts evil, and that hope rather than despair is our destiny. From his prison “cage,” he wrote,

“They won’t stop me even by taking hostages. Because nothing in life can have any meaning if you tolerate these endless lies… I’m never going to stop. I have no regrets about calling on people to take part in an unauthorized demonstration… I don’t regret for one second that I set out to do battle with corruption… I say again that I’m going to remain on my feet however long I have to, be it one meter from this cage, be it one meter inside this cage. I’m going to stand tall. There are more important things in this life.” (240-241).

Standing tall in the “more important things” of life, Navalny was uncowered. He insisted, “Dreams can become reality” (276).

As we’ve seen, the anchor of Navalny’s fearless commitment to truth and refusal to give up in the face of violent oppression was his trust in “good old Jesus.” Navalny always wrote about his faith with a healthy dose of humility and hilarity. But he believed that “there must be something more” and chose to trust Jesus’ promise: the kingdom of heaven belongs to those who are persecuted for the sake of justice. In fact, Navalny chose to see this persecution as proof that “we must be on the right path” (464).

From this perspective, the losers are really the winners. The oppressed are held in an unkillable belovedness and belonging that never dies, what Navalny called “the Kingdom of God.” With this faith, he declared in court, “The future is ours” (276). He echoed this unshakeable hope in his final smuggled Instagram message:

“[Putin’s lies] will crumble and collapse. The Putinist state is not sustainable. One day, we will look at it, and it won’t be there. Victory is inevitable. But for now, we must not give up, and we must stand by our beliefs.” (471)

Refusing to give up, Navalny said more simply, “Someday I believe it will all work out and everything will be fine… Russia will be happy” (115, 452). This humane happiness was the promise of Jesus’ Beatitudinal Way that Navalny walked to the end.

A Prophetic Witness for Us Today

As we enter into a new year and quarter century lurching toward increasing authoritarianism, the martyred Alexei Navalny endures as a prophetic witness for us today. He calls us into Jesus’s Beatitudinal Way of becoming humanely happy and resisting injustice. His work and writing presents a path for defying dictators:

- Tell the truth.

- Don’t be afraid.

- Organize.

- Remember that you’re not alone.

- Endure suffering with spiritual discipline.

- Protest oppression with playfulness.

- Embrace the mundane and cherish the simple things.

- Stay affectionate.

- Respect democratic rights for all, even amidst fierce disagreement.

- And never give up: everything will be okay in the end.

Navalny’s Jesus-inspired path bears witness to a new future in which all of us can “be happy.” With Jesus and Navalny, I enter into this new period of life with his confession: “Someday I believe it will all work out and everything will be fine.”

Happy New Year! And don’t forget to hug everyone at every opportunity you get!