What does it mean to be human? What is our core identity?

The way we see ourselves and others creates the world we see. Our basic vision of people shapes our attitudes and behaviors, and these end up structuring our relationships and societies.

From this perspective, the question of human identity is not a speculative fancy. It is immediately practical and deeply consequential for our lives, communities, and world.

The Bible introduced a rebellious vision of human identity that disrupted the assumptions of its cultural context.

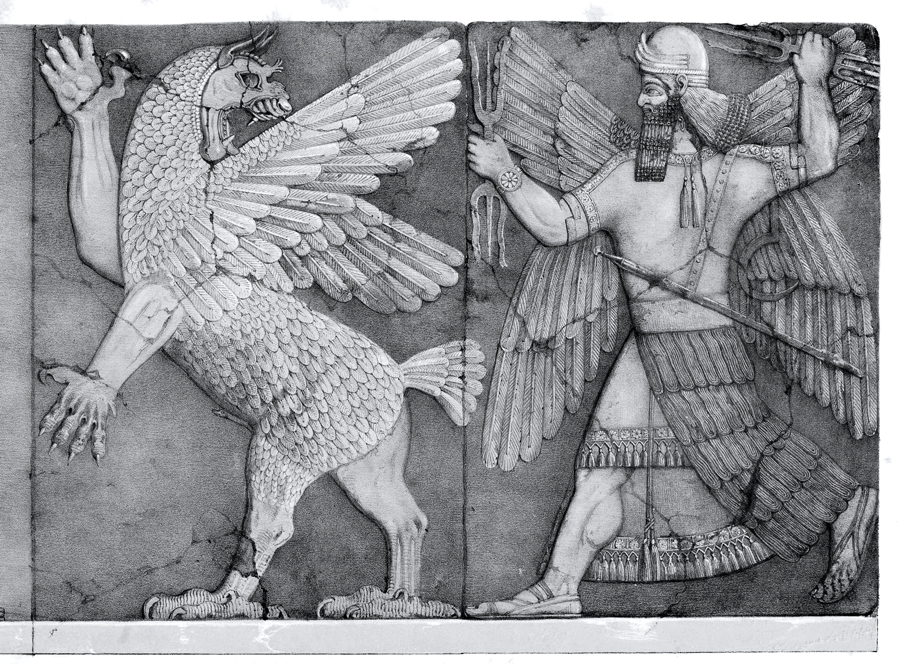

Ancient mythology constructed culture-making, society-structuring answers to the question of human identity. For example, see the cover picture above, the influential Mesopotamian myth Enuma Elish (“When on High”) explained that humans were made from the blood of a murdered god. The hero god Marduk (pictured as a warrior) slaughtered his rival goddess Tiamat (pictured as a dragon), and this is where we begin. According to this civilization-shaping narrative, human life is rooted in violence. (It’s also worth noting the gendered nature of this violence.)

Moreover, according to Enuma Elish, the purpose of human life is to labor as the gods’ slaves, building temples for their relaxation and farming food for their feasting. The gods themselves are “imaged” by stone idols, which embody the gods’ presence and power on earth in inaccessible temples. Kings and priests, who curated the idols, also “imaged” their gods, ruling on their behalf and maintaining their hierarchical system. The gods, represented by their images and elites, created a society of domination and slavery.

If you follow this story, human life is rooted in violence, structured hierarchically, and ultimately of little value – unless you’re a king or priest. (“Hierarchy” literally means “holy order.”) In many ways, this remains our vision of humanity today, even if we have abandoned its mythic framing and become subtler in masking our pyramid of value. Stories like Enuma Elish and their modern iterations hold tremendous power, because they naturalize special status for a few and subservience for the rest.

But the first, foundational chapter of the Bible tells a radically countercultural story about humanity.

Human life doesn’t originate from divine killing. We originate from divine communication. God speaks a word of creative invitation, and we are welcomed into the world without the murder of another. Peace is primal. Violence has no roots.

More radically, Genesis 1 says that each and every human is made in God’s image (Genesis 1:27). Stone idols don’t “image” God. The human person embodies and represents God’s presence and dignity in the world.

The implication is profound: to see and experience God, you do not need to go through an untouchable priest in an inaccessible temple to please idols that uphold a system of slavery. To see and experience God, you need simply to look into the face of your neighbor – whoever they are. They are God’s image. God is present in people.

It is striking that Genesis 1 makes no qualification about who carries the image of God like ancient culture did. The one exception is that Genesis emphasizes that both “male and female” equally embody God’s image (1:27). Otherwise, race and ethnicity are unmentioned. Hierarchy and rank are unmentioned. Class and money are unmentioned. Age and strength are unmentioned. They are all passed over in silence, as if they too have no roots in ultimate reality. In the beginning, when God’s original intent is sovereign, they are nothing.

Instead, each and every human – male and female – is made in God’s “image” and “likeness.” All people – whoever they are – embody and represent God in the world, undercutting every other claim to “identity.” According to Genesis, if you look at a human being and the first thing you see isn’t the image of God, you don’t understand humanity. You are primally blind and mistaking human fabrications for the ultimate fact about humanity. The human person is the heart of the universe and the face where God is found. This is why Genesis later insists that the one who attacks a human being has attacked God (9:6).

Further, Genesis 1 says that humans were created for a divine purpose: to share God’s creative work of organizing and enlivening the world (1:28). Humans aren’t slaves created to labor for divine architects of violence. Humans are co-creators with God, given the noble task of extending and stewarding God’s creative rule for a shared world. In this vision, every person is a king and priest. Hierarchy is undercut and abolished.

In short, Genesis 1 offers us an ancient vision of humanity that was and remains countercultural. Try to imagine if the first thing our eyes were trained to see in others was not some “identity” marker – whether ethnicity, religion, political party, or economic class – but to see the sacred image of God in all of its mystery and dignity. Imagine if our eyes’ first words on contact with others were, “I see you. You are God’s image. Whoever we are, we start together here. Everything else is secondary.”

The way we see ourselves and others creates the world we see. The problems and possibilities of our world originate in our vision of humanity, which frames our attitudes, behaviors, and systems in daily life.

Like an ophthalmologist, Genesis 1 removes cultural cataracts that justify violence, hierarchy, and devaluing others. And it gives us new eyes to see each and every person as God’s image created for life-giving service.

What are the idols of identity that block our vision today, and how can we retrain our eyes to see others as God’s image across every boundary?