How should we respond when we have conflict with others?

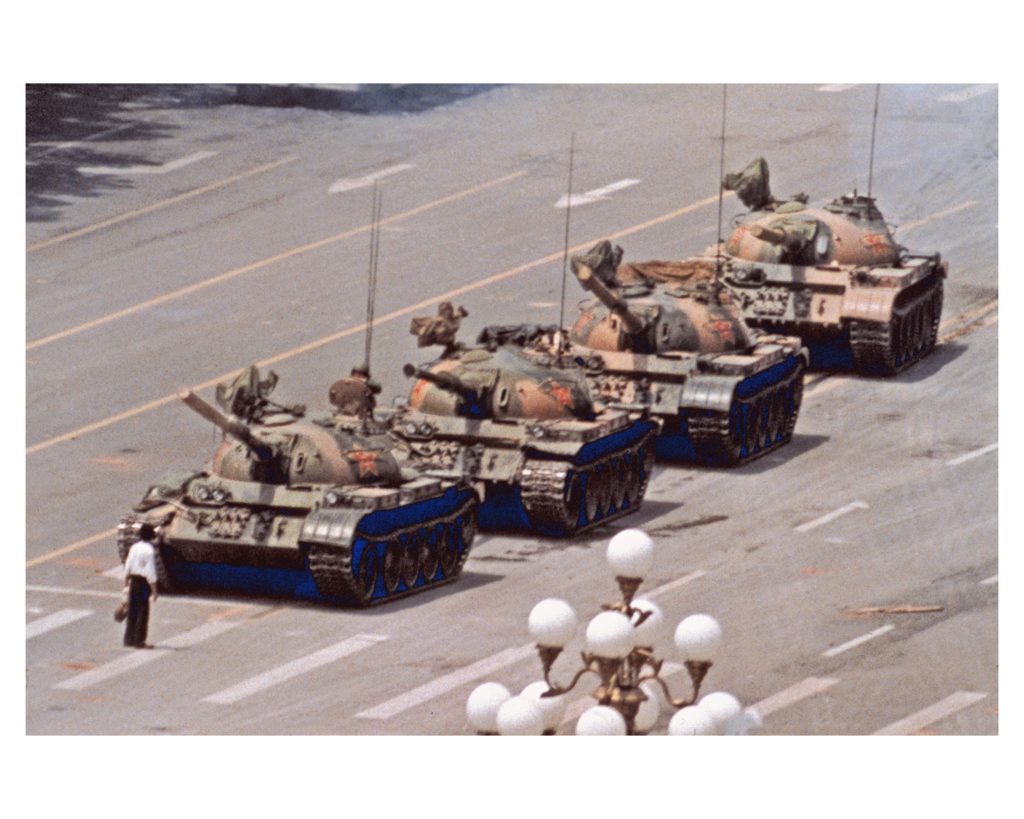

In recent years, more people have been killed in conflicts than any time since the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Much of this death has been inflicted in Ethiopia’s catastrophic civil war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Israel’s devastation of Gaza. Violence routinely tops our daily news headlines.

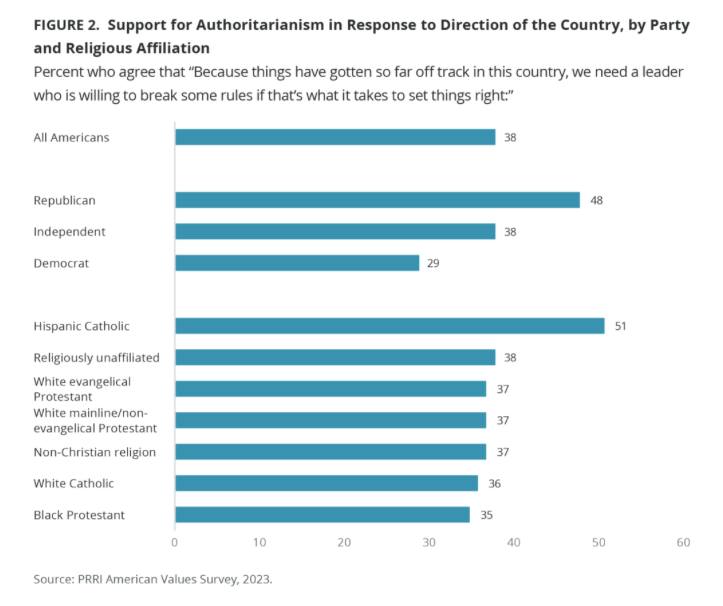

In the United States, Time Magazine reported in 2022 that almost half (47%) of Americans think that a civil war is “likely. PRRI’s 2023 “American Values Survey” offered similarly sobering insight into American society. According to this survey, more than one in three Americans (38%) believe that the country is so badly off track that they would support an authoritarian leader to try to fix it. More than one in three white Evangelicals (37%) agreed. Almost one in four Americans (23%) believe violence may be necessary to save the country, and almost one in three white Evangelicals (31%) agree.

These convulsive realities confront us with the urgent question I asked above: How should we respond when we have conflict with others? Said differently, how should we treat our enemies?

Jesus taught a countercultural but hopeful answer to this perennial but increasingly pertinent question: “Love your enemies.” We can appreciate the contemporary relevance of his teaching even more when we see it in its larger historical context.

Enemies in the Ancient World

Ancient human culture encouraged various responses to people perceived as enemies. But loving enemies was rarely among them. Let me simply mention four common approaches here:

1. Earthly Revenge: In the ancient world, King David represents the dominant response to enemies: take revenge and bring them “down to the grave in blood” (see 1 Kings 2:5-9). Here enemies are meant to be violently eliminated.

But there were also a few options in wider culture for practicing kindness or at least non-retaliation toward enemies.

But there were also a few options in wider culture for practicing kindness or at least non-retaliation toward enemies.

2. Ultimate Revenge: The Essenes, an apocalyptic Jewish group contemporary with Jesus, taught non-retaliation. They believed that this response would motivate God to punish their enemies even more severely in “the Day of Vengeance” (Community Rule 10:17-20). Here nonviolence is a deferred but everlasting stab in the back.

3. Moral Revenge: The Roman philosopher Seneca (4BC–65AD) was also a contemporary with Jesus. Seneca advocated for ignoring enemies. According to him, this response proves your moral superiority and apathy toward them, like an elephant disregarding a barking dog. Seneca asserted, “The most contemptuous form of revenge is not to deem one’s adversary worth taking vengeance upon” (On Anger 2:32). Here non-retaliation isn’t a form of mercy but apathetic mockery.

4. Evangelism and Advantage: Aristeas, a Jew living in Egypt a few generations before Jesus, thought that showing “generosity” toward opponents might “win them over to what is right and to what is advantageous to us” (Aristeas 227). His idea is that benevolence toward enemies has an evangelistic and strategic purpose: it helps you earn God’s favor and gain access to cultural power. This idea is reflected in other Jewish writings at the time, which makes sense in light of Jews’ minority status in hostile societies.

What is striking about each of these responses is that none of them has any real concern for the enemy or their wellbeing. The first option openly hates the enemy and seeks to destroy them. The second eagerly looks forward to enemies’ destruction but defers it to the future. The third belittles the enemy and is driven by prideful moral superiority. The fourth option is motivated by expanding one’s religion and gaining access to power.

These were the prominent options on the wider cultural menu for responding to enemies; direct violence was the main course.

Jesus’ Innovative Teaching

With this cultural context in place, try encountering Jesus’s words again for the first time:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those that persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous… God is kind to the ungrateful and wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.” (Matthew 5:43-45; Luke 6:35-36)

Notice three things in Jesus’ teaching.

First, Jesus was the first person in history to put these three words in the same sentence: “Love your enemies.” Sadly, as conflict escalates in our world, perhaps we can appreciate again just how strange these words would have sounded together. Jesus was boldly summoning people to imagine and embrace a response to conflict that many had never heard before: the right response to enemies is to love them.

Second, Jesus’ reasoning for this love wasn’t a deferred revenge, moral superiority, or even conversion and cultural power. His reasoning was entirely theological: God is generous to “the evil” and “the unrighteous” and “kind to the ungrateful and wicked.” God is an Enemy-Lover. If God is like that, then the truly divine life – the life of real freedom and hope º is to actively desire the wellbeing of our enemies.

Third, Jesus doesn’t leave his command to love our enemies ambiguous or merely aspirational. He names five practical pathways for loving our enemies: praying for them, doing good to them, blessing them, giving to them, and showing mercy or forgiving them.

Let’s look at each briefly.

Jesus’ Practices of Loving the Enemy

1. Pray: Jesus teaches us to pray for our enemies. When we pray for them (rather than against them), we ask God to be with them, to help them, and to heal them. This prayer shifts our consciousness away from resentment and revenge to compassion and care. Rather than seeing the other as hopelessly cut off from God and damned, which leads to demonizing them, Jesus invites us to bring them to God and intercede for their wellbeing.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a dissident theologian who was executed by the Nazis in 1945. He was the opposite of naive about human conflict. Bonhoeffer described the prayer Jesus taught as a “cleansing bath” that washes away the stain of hatred. Prayer is the premeditation of peace.

2. Do Good: Jesus doesn’t leave loving our enemies at “thoughts and prayers” alone. He tells us to move our bodies and actively “do good” for those who hate us.

Doing good requires creative imagination and practical action that helps others. When we do good, we recognize the other’s enduring dignity and do what we can to make sure that they have what they need to be well. In a sense, Jesus says that we should pray for our enemies (set our intention) and then become an answer to our prayer (act).

3. Bless: In the Bible, “blessing” is the word for divine happiness and favor. The ultimate prayer in ancient Israel was a request for God to “bless” Israel (Numbers 6:24). Blessing is often associated with joy, abundance, and peace (Deuteronomy 28:1-14).

In teaching us to bless our enemies, Jesus calls us to desire and declare divine flourishing for them. This takes us from praying and doing good for them to wanting them to be at their very best and fullest.

4. Give: But Jesus goes a step further. He teaches us to “lend to them without expecting to get anything back” (Luke 6:35). This action takes us deeper into personal sacrifice and more radically connects our prayer and practice. If we’re genuinely asking God to bless our enemies, then we should become partners in that blessing with our own resources.

Strikingly, Jesus explicitly names that we shouldn’t do this expecting to get something back. This would be just another transaction or an attempt to control our enemies. Philo, another contemporary of Jesus, encouraged lending to enemies because it “enslaves” them (On the Virtues §118). By contrast, Jesus teaches us simply to be generous to our enemies with no strings attached, like God is generous to all of us in giving us life and light.

5. Forgive: Finally, Jesus teaches, “Be merciful” (Luke 6:36) When we practice mercy or forgiveness, we declare to our enemies, “You are more important to me than the pain you caused me. I hold onto you and release your failure.”

This mercy prepares the way for new beginnings, because it frees us from being imprisoned in the past. In the midst of his execution, Jesus himself cried out, “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they’re doing” (Luke 23:34). Jesus invites all of us into this radical practice of hope for a new future.

The Paradox of Love

We often notice and name how parents and their children have a “family resemblance” in their physical features and/or personalities. For Jesus, these countercultural practices of loving our enemies are the “family resemblance” between God and God’s children. When we pray, do good, bless, give, and show mercy to our enemies, we embody the unmistakable traits of God. Jesus says that we imitate “our Father in heaven.”

This points to perhaps the most challenging aspect of Jesus’ teaching. He doesn’t see loving our enemies as optional or extra-credit for super-believers. Jesus sees loving our enemies as a basic requirement for having an authentic relationship with God:

“But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.” (Matthew 5:44-45; see Luke 6:35)

The reason for Jesus isn’t because God is vindictive or vengeful. It’s actually the opposite: “God is kind to the ungrateful and wicked.” If this is who God is, then we won’t want a relationship with God unless we want our enemies to be well. This is the paradox of love: we only exclude ourselves from full belonging with God when we exclude others from this belonging.

This teaching is extra challenging, because Jesus wasn’t speaking to Seneca and other Greco-Roman elites who saw themselves as proud elephants ignoring barking dogs. Jesus was speaking to minorities and oppressed people in the heartland of an occupied territory who were intimately familiar with suffering (Matthew 4:23-25; Luke 6:17-18). And still Jesus commanded them to love their enemies. With any other response, they would simply mirror their enemies’ enmity and aggression in a hopeless spiral.

It’s no wonder, then, that Jesus began his public movement with the call, “Metanoieta!” This Greek verb means to completely change how we think (Matthew 4:17). Jesus was calling for a worldview overhaul, a paradigm shift, a total conversion in how we love.

It’s also no wonder that the crowds who heard Jesus’ teaching were “amazed” by his “authority” (Matthew 7:28). They were among the first people in history to hear this unprecedented description of God’s character and call to love everyone unconditionally. They found it awe-inspiring.

Jesus’ Original Mission

Any leader of a team knows how important it is to stay crystal clear about your mission. “Mission drift” is all too easy and can be disastrous.

The same is true for those who want to follow Jesus. If we’re not careful, we’ll misunderstand and derail the actual mission that Jesus has given us. For example, as I noted above, around one in three white American Evangelicals say that they would support an authoritarian leader and think that violence may be necessary “to set things right” in the United States.

Look at Jesus’ last words to his first followers. This is where Jesus defines their core mission:

“Go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” (Matthew 28:19-20)

Jesus doesn’t commission his disciples to convince people to identify as “Christians.” He also doesn’t tell them to build and attend churches. Jesus commissions his disciples to educate and immerse people in a totally new way of thinking, feeling, and acting. In short, “to obey everything I have commanded you.”

And what did Jesus command? As we’ve seen, Jesus made this clear:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those that persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.” (Matthew 5:43-45)

At its heart, then, Jesus’s Great Commission was really a call to embody and expand his innovative vision of God’s enemy-loving character and command across the world. That’s the mission: practicing and promoting what Jesus actually commanded us.

By Jesus’s own standard, entire countries can identify as Christian, go to church, and affirm that “Jesus is Lord!” But if we aren’t actively committed to loving our enemies, Jesus’ mission remains an unfinished project and we’ve missed the point.

So how should we treat our enemies in our time of escalating conflict?

So how should we treat our enemies in our time of escalating conflict?

Jesus’ answer remains countercultural and hopeful still today: we should love our enemies. Love alone can heal hatred and create a new future. We can practice this radical love by praying for our enemies, doing good to them, blessing them, giving to them, and being merciful.

“Do this,” Jesus promised, “and you will flourish” (Luke 10:28).

***

Learn more about the ethics of enemy love in my book Reviving the Golden Rule: How the Ancient Ethic of Neighbor Love Can Heal the World.