Dear friends,

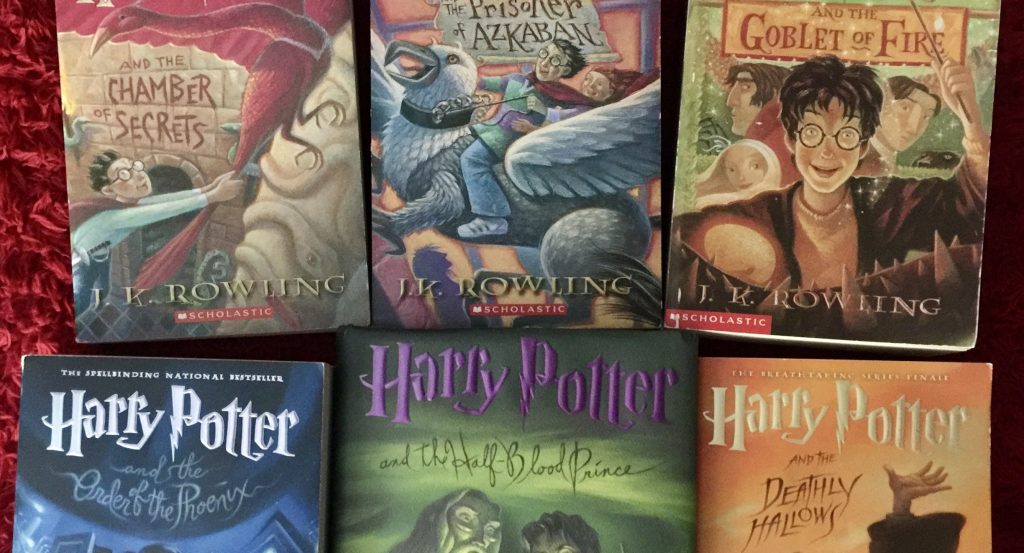

I recently finished reading the Harry Potter series, which was published between 1997 and 2007. My late PhD adviser Jean Elshtain always spoke so highly of these seven books, and now I know why.

In this essay, I want to share with you some of what I’ve discovered in the Potter universe. Perhaps these reflections will stir up treasured memories for you, or spur you on to read the series for the first time, or simply enrich your own moral imagination. Spoiler alert: I discuss a lot of plot details and endings below. If you want to jump around, I bold the key topics and characters.

For starters, these books deserve to be the best-selling story in history, which they are with over 500 million copies in print. They’re fundamentally about ethics — about good and evil, love and power, loss and resurrection. They speak to the human longing for goodness, joy, and togetherness despite evil, hate, and murder.

As such, they’re a moral myth of good and evil for a new generation haunted by nihilism, the idea that says with Lord Voldemort, “There is no good and evil. There’s only power and those too weak to seek it” (Sorcerer’s Stone, 291). J.K. Rowling clearly believes that good is real and that evil’s power is passing away, despite all the maddening evidence to the contrary.

For her, goodness leads to “a soul that is untarnished and whole,” while evil leads to “a maimed and diminished soul” (Half-Blood, 509-511). And goodness is always stronger than evil, “like a tongue on frozen steel, like flesh in flame” (Deathly, 685). But the only way to healing is remorse or what is often call repentance: “You’ve got to really feel what you’ve done. Apparently the pain of it can destroy you” (Deathly, 103, 741).

These books are not only brilliant in substance but also beautiful in style. Rowling is one of the most delightful authors I’ve ever read. Her artistry with the English language – her capacity to pick the perfect words and put together the most elegant phrases and sentences – amazes me. For example, after Dumbledore dies, she writes of the phoenix’s “stricken lament of terrible beauty” (Half-Blood, 614). Haven’t we all felt that but perhaps without the words to name it?

The core theme of the Harry Potter story is othering, which means seeing and treating others as unrelated or less than ourselves. “Pure-blood” wizards and witches think they’re superior to a whole host of other humans and nonhuman creatures: Muggles (non-magic folks), half-bloods or “Mudbloods” (people of mixed Magic and Muggle parentage), Squibs (people of magical ancestry who can’t perform magic), giants, werewolves, goblins, merfolk, etc.

Othering leads to dehumanization, and we overhear bully wizards at school say, “Muggles are like animals, stupid and dirty” (Deathly, 574). The Dark Lord Voldemort articulates where this goes: “We shall cut away the canker that infects us until only those of the true blood remain” (Deathly, 11). By contrast, Harry’s godfather Sirius Black insists, “If you want to know what a man is like, take a good look at how he treats his inferiors, not his equals” – essentially a quote from Nelson Mandela (Goblet, 525).

And this is what makes Professor Dumbledore both stand out and fit in: he has respect for all of these “others,” and he doesn’t think wizards are superior to any of them. Rowling calls him “the champion of commoners, of Mudbloods and Muggles” (Goblet, 648). His eulogist says, “he could find something to value in anyone, however apparently insignificant or wretched” (Deathly, 20).

But this learning comes at great cost: “his determined support for Muggle rights gained him many enemies” (Deathly, 17). Hermione’s care for house-elves – “how sick it is, the way they’ve got to obey?” (Deathly, 197) – and Harry’s love for Hagrid (a half-giant) and Lupin (a werewolf) are other examples of how othering is resisted in the Potter universe. Luna’s father’s name is another clue: Xenophilius Lovegood, a Greek code that means love of the other is good love. (Note that in Romans 12, Paul writes, “Practice xenophilia.”) Interestingly, Xenophilius is the publisher of The Quibbler, a newspaper that dissents against the propagandistic othering of the Daily Prophet.

As the story unfolds, we see that othering is the crucial weapon and blind spot of evil, a chink in Voldemort’s armor:

“Of course, Voldemort would have considered the ways of house-elves far beneath his notice, just like all the purebloods who treat them like animals… It would never have occurred to him that they might have magic that he didn’t.” (Deathly, 195)

And thus deliverance comes and hope is reborn through a lowly house-elf, more than once (Deathly, 474).

Dobby’s self-abuse and Kreature’s hatred for freedom show the mutilating power of othering and how it comes to imprison us from the inside, making us prisoners of our pain until we accept love. As Dumbledore laments, “Kreature is what he has been made by wizards, Harry” (Goblet, 832). Note that Harry himself doesn’t even think to give Kreature a Christmas present (Half-Blood, 339). Dumbledore goes on to make perhaps the most insightful statement about othering in the entire series regarding Harry’s godfather Sirius:

“Sirius did not hate Kreacher. He regarded him as a servant unworthy of much interest or notice. Indifference and neglect often do much more damage than outright dislike… We wizards have mistreated and abused our fellows for too long, and we are now reaping our rewards.” (Goblet, 834)

This othering indifference, neglect, and abuse is why the “others” enlist to fight with Voldemort. They’ve suffered at the hands of the “good” wizards long enough, and they wrongly but understandably believe that he can give them a better life, even as he only uses them as tools of death.

Rowling’s moral universalism is expressed by the Black wizard Kingsley:

“It’s one short step from ‘Wizards first’ to ‘Purebloods first’ and then to ‘Death Eaters first.’ We’re all human, aren’t we? Every human life is worth the same, and worth saving.” (Deathly, 440)

In the end, this is what salvation looks like in Rowling’s new creation, her version of Revelation’s multi-ethnic, multi-species feast in heaven:

“McGonagall had replaced the House Tables, but nobody was sitting according to House anymore: All were jumbled together, teachers and pupils, ghosts and parents, centaurs and house-elves, and Firenze [a centaur] lay recovering in a corner. Grawp [a giant] peered in through a smashed window, and people were throwing food into his laughing mouth.” (Deathly, 745)

Dumbledore is an astonishingly good character, and this is his goodness: he humiliates no one and feels compassion for everyone (Half-Blood, 262). Even when he addresses the Dark Lord Voldemort or his near-murderer Draco or the enraged Harry Potter, Dumbledore is respectful, honoring, and patient. He understands that everyone, even Voldemort, has a history – sometimes an extremely painful history – and deep fear of loss.

Dumbledore doesn’t make himself more by making others less, even when he needs to be direct and severe. He never puts another down but attempts to raise them up, even to the bitter end, which isn’t the end as we’ll see below. To Malfoy he compassionately appeals, “Come over to the right side, Draco….you are not a killer” (Half-Blood, 592).

And Dumbledore is able to admit his mistakes, apologize, and ask for help from his juniors. To Harry he says, “I make mistakes like the next man” (Half-Blood, 197). Indeed, in the end, he’s not triumphant but remorseful: “I crave your pardon, Harry” (Deathly, 713).

This is Dumbledore’s real magic: he’s confident but humble, insists on seeing the best in others, and believes that love is stronger than any magic. And thus he is unrushed, unafraid, and kind – and healthfully suspicious of himself: “I had learned that I was not to be trusted with power” (Deathly, 717).

Harry Potter is a figure who embodies the triumph of nonviolence. To the end, Harry never uses the Killing Curse and never kills anyone. He always disarms or stuns his opponents; in fact, his nonviolent magic becomes his telltale sign, which endangers his own life:

“I won’t blast people out of my way just because they’re there. That’s Voldemort’s job,” he protests (Deathly, 70-71).

Harry goes so far as to save the lives of his worst enemies: Peter in the Shrieking Shack, Malfoy in the Room of Requirement, and Voldemort himself in the Forbidden Forest.

Eventually, Harry needs to learn that death and dying are not to be feared, as Dumbledore repeatedly promises. His liberation is found in letting go of violent power and accepting death. In this way, Rowling fundamentally pictures Harry like Jesus: he lays down his life for his friends, and then he discovers that death is not the end but a door to resurrection (John 15:13): “The only way out was through” (Deathly, 541). Or as a post-death Dumbledore cheerfully assures a recently murdered Harry,

“I think we can agree that you are not dead – though, of course, I do not minimize your sufferings, which I am sure were severe.” (Deathly, 712)

And thus Dumbledore is proven right: “It is the unknown we fear when we look upon death and darkness, nothing more” (Half-Blood, 566). His final words to Harry are for me perhaps the most beautiful in over four thousand pages of story:

“You are the true master of death, because the true master does not seek to run away from Death. He accepts that he must die, and understands that there are far, far worse things in the living world than dying… Do not pity the dead, Harry. Pity the living, and, above all, those who live without love.” (Deathly, 721-22)

In the end, our bodies are like the Snitch containing the Resurrection Stone, which bear the riddle, “I open at the close” (Deathly, 134). This is why Rowling puts Paul’s key text about the resurrection on Harry’s murdered parents’ gravestone: “The last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26). As Hermione explains, “It means…you know…living beyond death. Living after death” (Deathly, 328).

I find it extremely profound that books that appear to be all about magic relentlessly decry violent force and elevate nonviolence to the highest position of honor. Under the tutelage of Dumbledore, “Harry had long since learned that bangs and smoke were more often the marks of ineptitude than expertise” (Half-Blood, 558). Or as Snape says to Harry,

“You wasted your time and energy shouting. You must remain focused. Repel me with your brain and you will not need to resort to your wand… Master yourself! Control your anger, discipline your mind.” (Goblet, 535-36)

But Harry’s nonviolent struggle isn’t sugarcoated or cheap. The books are emotionally intense, the story is devastating. Professor Moody says, “It’s my job to think the way Dark wizards do,” and this is what Rowling requires us to do (Goblet, 280). We watch as Harry becomes more and more traumatized, enraged, and unhinged by the deception, betrayal, and death he suffers: “Harry’s scream of horror never left him… He doubted that he would ever feel curious again” (Half-Blood, 596, 631).

Still, Dumbledore sets an astonishing example of emotional composure, centeredness, and patience, which Harry slowly grows into. We witness that evil, violence, and loss are devastatingly wounding, disturbing, mutilating, and deadly. But real maturity is found in patience, kindness, gentleness — essentially the fruit of the Spirit (Galatians 5). This inner work is essential to nonviolence.

Voldemort is a brilliant character and the story’s arch villain. He both is and is not satanic. Most basically, he’s an orphan, a vulnerable child that never experienced love. We find out through Dumbledore’s attention to the past that Voldemort’s Muggle father abandoned him and that his magical mother died of heartbroken poverty. Thus Voldemort grew up in an orphanage.

And without love, Voldemort becomes a monster of power: friendless, unforgiving, manufacturing loyalty through fear, addicted to being exceptional, unable to accept his own ordinariness, a killer for greatness and collector of trophies. For me, perhaps the most profound aspect of Voldemort’s history is his rejection of his own name “Tom Riddle.” For Voldemort, “Tom” is such a common name, and Voldemort despises being associated with others and thus being “ordinary.” Greatness – not goodness – interests Voldemort (Half-Blood, 276-77).

And thus power is everything for Voldemort, and this is the heart of his nihilism. He kills his own father and says to Harry, “I am now going to prove my power by killing you” (Goblet, 658). To avoid death, he endlessly produces death. And yet, at the end, he’s still just a wounded child – “left, unwanted, stuffed out of sight, struggling for breath” – who’s unable to accept that he’s safe and okay in all of his vulnerability and mortality (Deathly, 704, 707).

In this subtle way, Rowling implicitly asks her reader, “Isn’t every human ‘monster’ really a wounded child who’s never made peace with their vulnerability? How are you processing your vulnerability and mortality?” In so many ways, Voldemort is inside all of us. Here the intimate connection between Voldemort and Harry is so insightful. In the end, Voldemort shows that addictive dependence on power and violence are suicidal. Violence kills us. Dumbledore unmasks this with a delicate question: “You call it ‘greatness,’ what you have been doing, do you?” (Half-Blood, 443).

Still, evil is not total, and people can be redeemed. This is the significance of Draco Malfoy, the teenage villain in the story. He sneers and slurs others and incites conflict. He desperately wants to be the tough guy who claims the glory of murdering Dumbledore. But Draco can’t bring himself to do it. Similar to Voldemort, he’s driven by his own desperate insecurity and fear of being rejected or harmed by the bigger bully, but that’s not his core. In the end, arch rivals are reconciled.

In many ways, Harry’s dad James Potter is the reverse archetype of Malfoy. He’s a hero with ugly secrets. Harry worshiped him but found out that he was arrogant and cruel when he was younger. In fact, witnessing the way James humiliated Snape broke Harry’s heart and generated empathy for his enemy (Order, 650).

Overall, Rowling is very much not a Manichaean or someone who thinks that evil is equal to goodness in an eternal struggle. Still, she sees moral complexity in all of us, blurring the lines between heroes and villains. In our age of clean us vs. them identities hardened by moralistic certainty, Rowling’s complex moral imagination is prophetic and refreshing. Decrying our denial and extremism, Harry protests to the Minister of Magic,

“You never get it right, you people, do you? Either we’ve got Fudge, pretending everything’s lovely while people get murdered right under his nose, or we’ve got you, checking the wrong people into jail and trying to pretend you’ve got ‘the Chosen One’ working for you!” (Half-Blood, 347).

Deloris Umbridge is perhaps the most sinister character in the story, even more so than Malfoy or Voldemort. She smiles fakely and speaks sweetly. She dresses in pink, adores kittens, and constantly laughs. And she insists that evil is unreal and that being prepared to fight it is unnecessary. But behind her innocent facade, she trusts power and craves power. And she is ruthless and cruel in her pursuit of power, with no tolerance for questions or dissent. The kitten-lover doesn’t hesitate to torture children, and thus are many of our leaders.

Rita Skeeter, the journalist for the Daily Prophet newspaper, is a great satire of government propaganda and profit-driven fake news. She tells people what she thinks they want to hear and what she thinks will make her rich and famous (Order, 567). It’s through Skeeter that we discover Rowling’s gritty epistemology: people generally believe what comforts and excites them, not what is true. Conversely, people willfully disbelieve what makes them uncomfortable or afraid, even when this ultimately endangers and destroys us.

Rowling brilliantly underscores how we’re often wrong and how being wrong can actually save us. Severus Snape is the key figure here, as well as Sirius Black – both branded as vicious villains but wrongly so. Harry is dead certain that Snape is a worthless murderer, and what makes this so powerful is that Snape genuinely hated Harry’s dad and fiercely resented Harry. There’s no love between them, except perhaps Lily’s eyes in Harry’s. But Dumbledore was still right to trust Snape, a sign that people can actually change, and Harry was wrong to doubt Snape — and being wrong ended up saving Harry’s life. In a brilliant conversion of enmity to admiration, Harry ends up naming his son after Snape, the man he had so totally despised. Our enemy can become our child’s namesake.

From start to finish, the books are about loneliness and the saving power of friendship. Voldemort’s mother Merope shows how being unwanted and abandoned kills the magic in us and drives us to death. Conversely, what saves us is not being the strongest or the smartest or even the most virtuous but being together, loving one another, and expanding our circle of inclusion. As Harry says to Cedric, “Let’s just take it [the Champion’s Cup] together” (Goblet, 634), or as Ron says to Harry, “We’re with you no matter what happens” (Half-Blood, 651). Rowling writes,

“The mere fact that [Ron and Hermione] were still there on either side of him, speaking bracing words of comfort, not shrinking from him as though he were contaminated or dangerous, was worth more than he could ever tell them.” (Half-Blood, 99)

Hermione, endlessly endearing and academic, is the most fiercely loyal friend in Harry’s life.

It’s beautiful to watch how Dobby, Neville, Luna, and Ginny – initially fringe characters and outsiders – become crucial friends along with Harry, Ron, and Hermione. We learn not to underestimate or ostracize the strange, silent, and uncool. It’s also fascinating to see how Ron is a fairly prejudiced, dull character; sometimes the friend we need still has a lot of growing up to do. As Dumbledore gently counsels the heroic savior who thinks he can go it alone, “You need your friends, Harry” (Half-Blood, 78).

In so many ways, these books affirm the goodness of our bodies and how we are fundamentally physical, embodied creatures. I love that Fawkes’ tears have healing powers (Chamber, 207). All tears when freely cried have healing powers. Lily’s love lives on in Harry’s skin: “Voldemort could not bear to reside in a body so full of the force he detests” (Order, 844). Dumbledore figures out how to enter Voldemort’s cave, not by magic, but by touching the rock with his hands and patiently looking at it with his eyes (Half-Blood, 558). Dumbledore cheerfully warns Harry that Voldemort is wrong to fear his body: “There’s nothing to be feared from a body, Harry” (Half-Blood, 566). Even after death, Harry still has a body.

In this way, Rowling suggests that our goal is not to get beyond our bodies but to embrace them. In fact, the most solemn moments of the books completely disavow magic in reverence for the body’s finite strength, for example, Dobby’s burial. Again and again in crucial moments, a character is told to sleep or eat food or enjoy chocolate. (“A full stomach meant good spirits; an empty one, bickering and gloom,” Deathly, 287). The body is good and will be resurrected (Goblet, 863-64). Still, as Dumbledore brilliantly says, “It is necessary to start with your scar” (Goblet, 827). Our bodies carry our trauma, and we must not ignore this.

As I’ve suggested already, this story is all about the movement away from greatness to goodness (Half-Blood, 443; Deathly, 508, 568, 716). Its climax is a brilliant anticlimax: Harry doesn’t become the next Headmaster of Hogwarts or the Minister of Magic or Lord Harry. He becomes a husband to his friend Ginny and a dad to children who won’t grow up with the trauma he suffered. The best-selling story in history doesn’t end with a celebrity but a father.

In this way, Harry is the anti-hero we need today. He embraces ordinary life and cares about little people. He wants goodness, not greatness. His abandonment of the Elder Wand is utterly brilliant; I write about this in my forthcoming book Practice Flourishing: The Spirituality of Jesus.

The Dementors were the most striking monster in the Potter universe for me. They are hooded, ghostly creatures that survive by sucking all joy and hope out of people’s faces, which is darkly known as the Dementor’s Kiss. They are literally soul-suckers (Azkaban, 237).

These are certainly the monstrosities I fear the most: the shadowy figures that suck joy and hope out of my soul. Interestingly, the Ministry of Magic depended on them for safety, much like we rely on violent terror to create a false sense of security in our world, only for them to backfire on us. How many of us find security in what terrorizes others, only for it to turn on us in the end? In many ways, this is a subtle critique of the so-called War on Terror.

The the only way to fight Dementors is with the Patronus charm. You perform this charm by saying “Expecto Patronum!” which means “Expect a guardian” and then recalling a powerful memory of deep joy. This is utterly brilliant and ruggedly practical: what saves our souls from despair is the active, intentional memory of joy. Gratitude is our guardian. This reminds me of Paul saying in prison “Rejoice in the Lord always” (Philippians 4:4). Lily and many friends have been my Patronus when Dementors are destroying my soul.

Some of the most moving scenes for me are when Harry discovers his dead loved ones are still with him. This is where Rowling is radically, defiantly hopeful. We fear that we’re alone, abandoned, cut off. But we’re not. Our dead loved ones are somehow still near us, with us, whispering words of affection and confidence, just across the veil: “You’ve been so brave,” Lily tells her son. (I was in tears reading this.) Harry fearfully asks his dad, “You’ll stay with me?” and James answers back, “Until the very end.” Rowling tells us,

“They acted like Patronuses for him… Their presence was his courage… The dead who walked beside him through the forest were much more real to him now than the living back at the castle.” (Deathly, 699-701)

We will be together again, even after devastating loss has unbearably scarred our souls

The end of Rowling’s million-word series brilliantly alludes to Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love: “All was well.” I thought this conclusion was entirely perfect. In many ways, the whole series is a narrative of hope. To the final three words, Rowling defiantly rebels against the cultural tide of materialism, cynicism, and the finality of death. No, we will live again in goodness beyond death, she says. Our lives go on. As the resurrected Dumbledore says, “Don’t pity the dead, Harry. Pity the living, and above all, those who live without love.”

Where is God in Harry Potter? Dumbledore isn’t exactly the God character, though he’s certainly the key elder figure of wisdom and maturity who’s passed beyond the fear of death. Harry is definitely the Christ figure but not God.

It seems to me that love itself is God in Rowling’s universe, or as the Apostle John said, “God is love” (1 John 4:8, 16). This is woven throughout the story.

After Harry saves the life of the ratlike man who betrayed his parents to death, Dumbledore reveals to Harry, “This is magic at its deepest, most impenetrable, Harry” (Prisoner, 427). Voldemort himself expresses this divine insight as he faces a fearless Dumbledore: “love is more powerful than my kind of magic” (Half-Blood, 444; Deathly, 709-10). This moment of dialogue between an underwhelmed Harry and faithful Dumbledore is key:

“‘So, when the prophecy says that I’ll have “power the Dark Lord knows not,” it just means – love?’ asked Harry, feeling a little let down.

‘Yes – just love,’ said Dumbledore.” (Half-Blood, 509)

Overall, people who think these books are harmful to authentic faith have a very limited understanding of faith and probably haven’t actually read these books. At heart, the books are not about magic but morality. And the morality is essentially Christian morality: love others, even the strange and unwanted ones; sacrifice yourself for others, even when you’re burning with hate and lusting for power; trust God is better and stronger than evil and death itself; and live in hope and joy, even when you’re hurting.

Or as Professor Dumbledore tells his students,

“Lord Voldemort’s gift for spreading discord and enmity is very great. We can fight it only by showing an equally strong bond of friendship and trust. Differences of habit and language are nothing at all if our aims are identical and our hearts are open.” (Goblet, 723)

This profound and practical moral imagination has never been more important and urgently needed than it is today in our time of polarization, conflict, and war. It can heal our othering and energize our love, even beyond the author’s own intent.