Dear friends,

Today marks 20 years since my best friend Matt Powers was killed in a car accident. Matt was only eighteen; I was seventeen.

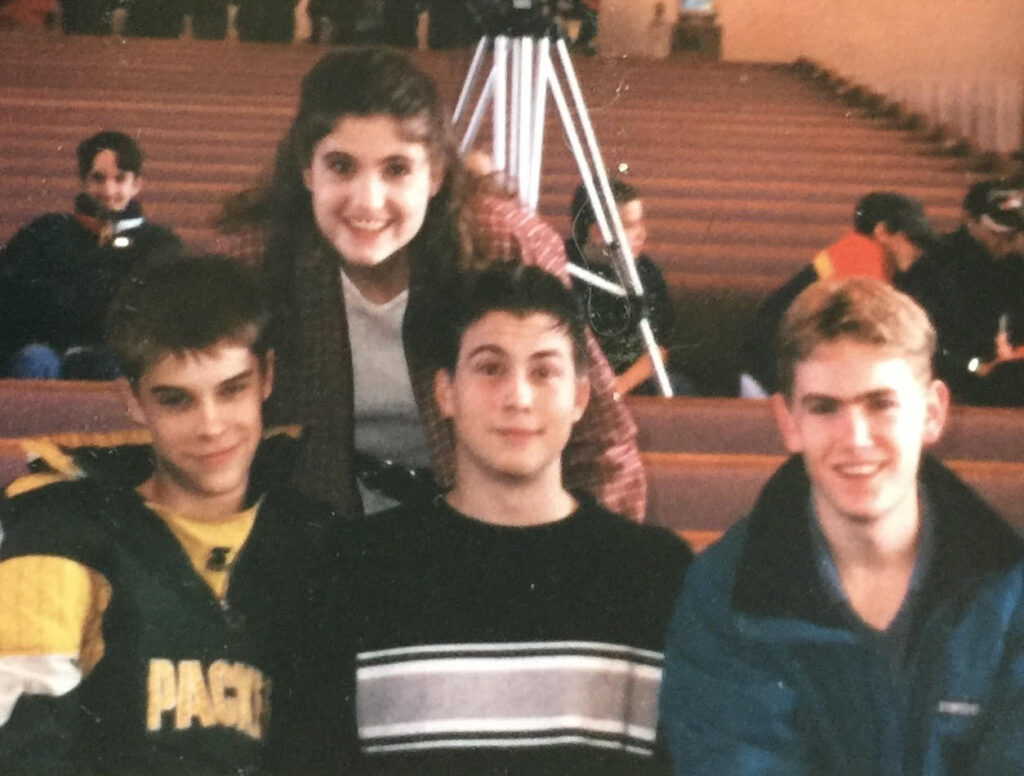

I love and miss Matt. He was a person of infectious joy. His smile was so genuine and his mirthful laughter — I can still hear it dancing through the air today. Matt was a fierce competitor, and he was working hard to become a personal trainer. But Matt was extremely kind and made others feel included. He loved God and loved his neighbor and loved me. We did everything together — sleepovers, birthdays, sports, road trips, music, church, life.

Today, if you’re grieving, I want to say you’re not alone. Maybe your grief started recently. Or maybe it started decades ago. You do not need to deny or suppress your grief.

In 2019, I was at a therapist’s office at the University of Chicago talking about Matt and weeping. Through my tears, I asked Dr. McPherrin, “Do you think I’m still grieving Matt’s death?” He answered that my tears were answering my question.

I’ll never forget this moment: my body and soul were grieving the death of my friend, but my mind was still resisting and distancing this grief. Somehow I couldn’t accept my grief. But that day, eighteen years after Matt died, I began accepting my grief and discovered that it is good to grieve.

As I look back, I‘m learning to welcome the presence of God into my memories of that horrible night. I am working on re-remembering.

God was suffering with us in the waiting room where I heard such raw pain and despair and anguish. God was suffering with me when I went inside and saw Matt’s dead body on that hospital table — my beloved friend, injured, cold, motionless. God was suffering with us outside the hospital as so many friends gathered and spoke words of confusion, desperation, love, encouragement, hope, togetherness.

I’m learning to believe that God is with us in our suffering — gently holding us, preserving our tears, whispering comfort and hope. And I am learning to re-remember Matt’s death not as a time when God was absent but when God was with us in one of the most painful, traumatic, unbearable moments of our lives.

Third, as I love and miss Matt twenty years later, I’m learning to trust God with what is most precious to me. I am increasingly aware of my vulnerability, my fragility, the possibility of losing people and things that I love. I am learning to welcome God’s presence into this vulnerability — to not hide it or build a wall around it but to open it, face it, and invite God into it.

We are all dying. The days we live, the plans we make, the things we build, they are all numbered and will come to an end. Vulnerability is the secret of our lives; it’s one thing that is universally shared and yet intimately our own.

When David says, “Praise the Lord, O my soul, and all that is within me” (Psalm 103:1), I also want to praise God with my vulnerability, my ache of grief, my awareness that I and Lily and my parents and my siblings and my dearest friends and everyone I know will experience what Matt experienced. We will all have to let go and trust. This is the one certainty of human existence.

I am learning to face death with hope. I believe our lives in this world are just the first step on our journey with God and one another. Death is like walking through a door to a new room. It is a transition. And since I believe God created us because God loved us even when we were nothing, I believe God will hold us, heal us, and set us free from the bondage to decay even when are return to nothing (Romans 8:18-21).

I can’t wait to meet Matt again. I can’t wait to see his smiling face, to hear his laughter, to walk with him or play the guitar together. I don’t believe this hope is wishful thinking or a dishonest coping mechanism. It is the oxygen of our souls. My burning for it shows that I was made for it, just like my lunges were made for breath and my heart for blood.

Loving and missing Matt, and facing the intimate reality that we are all dying, points me toward the wisdom of gentleness. When Matt died, the only thing we could do was hold each other. Gentleness was the only language that made any sense. The thought of anyone else experiencing this grief — even my worst enemy — was sickening and saddening to imagine. It still is to this day.

The medieval political theorist John of Salisbury asked a question in his work Policraticus that I will never forget: “Why are dust and ashes arrogant toward dust and ashes?” Salisbury’s point was that our arrogance toward one another is absurd when we remember that we are all dying. Our destiny — universally shared, intimately our own — is not triumphant victory but radical vulnerability, final surrender, and total dependence on Another’s love to save us.

Matt was a body builder with huge, rock-hard muscles. But what I remember today is his gentleness, his kindness, his compassion when others were hurting. Gentleness is not weakness; it is the greatest form of strength. I believe it will endure forever, at home in the gentleness of God who grieves with us and promises us the gift of life after death.

I want to end this reflection on my friend’s precious life by looking inside my own soul. I have wept as I wrote these words, and I want to better understand why. Why, twenty years later, does my friend’s death still make me cry?

First, perhaps I simply miss Matt — his face, his smile, his laughter, his enormous hands, his loving heart, his caring presence. Perhaps my tears are the language of my body saying, “Matt, I miss you.”

Second, there is something primally painful about remembering seeing Matt’s dead body on that table, the raw sorrow of lowering his body into the earth, the indescribable sadness of his parents, and the radical vulnerability of facing that we are all dying and that all we grasp onto so fiercely must be held loosely and finally released. Perhaps my tears are the language of my soul saying, “Andrew, this is frightening and painful; go slowly and be gentle.”

Third, perhaps my tears are my first experience of heaven’s river of life. Jesus said, “Out of you will flow rivers of living water.” The last book of the Bible speaks of the river of life and how its water will heal humanity. Søren Kierkegaard wrote about God’s “covenant of tears” with the grieving. Perhaps my tears are a divine protest and promise inside me interrupting the utter normalcy of death: “Andrew, you were made for life not death; let grief wash over you and continue hoping; healing is coming.”

I’m sure there are more hidden messages in my tears. I want to listen to them. My instinct is to be embarrassed when I cry and to suppress my tears. But I am slowly learning that I don’t need to be embarrassed or restrain my tears. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler were profoundly right in On Grief and Grieving: “The truth is that tears are a symbol of life and can be trusted.” God, what are they saying? Teach me to listen.

Matt, I love and miss you. I’ve carried you in my heart for the last twenty years. I weep for you and cherish you today. Thank you for loving me and sharing your life with me. One day, the door will open, Lily and I will step through, and we will all be reunited in heaven.

“My Father’s house has many rooms; if that were not so, would I have told you that I am going there to prepare a place for you?” Jesus (John 14:2)

Matthew Jacob Powers: December 11, 1982 — March 29, 2001 — resurrection