Shema

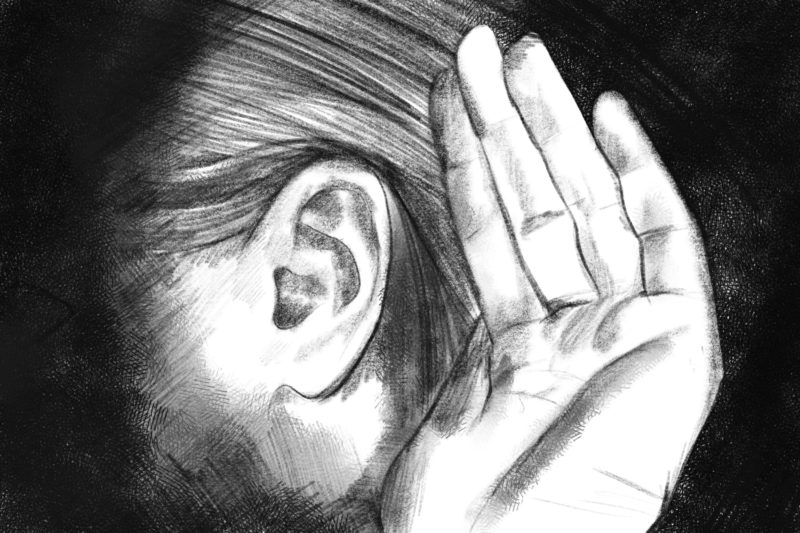

Stop and listen for a moment

I have always been amazed that God’s first command for ancient Israel began with the simple word listen (Deuteronomy 6:3-4). This command is repeated dozens, if not hundreds of times, throughout the pages of the Hebrew Bible. For many Jews to this day, shema – the Hebrew imperative listen – names the very essence of authentic religion.

Listening is an act of faith that positions the listener in attention and readiness for transcendence, for what stands outside and beyond the listener’s knowledge and control. The one who listens can neither force the other to speak, nor can they foresee what the other will say. Instead, their listening is an active, risk-taking embrace of raw vulnerability to what is unknown and must be revealed by someone other than myself.

Thus, the open ear says,

Here I am. I don’t know what you will say or what it will mean for me. But I’m listening. You are free to reveal yourself.

In the Hebrew Bible, this willingness to listen is the singular precondition for having a relationship with the Creator of all things. If you want to meet God and not a fake substitute (what the Bible calls an “idol”), you must be willing to listen, to enter into that vulnerable posture of total openness to what transcends yourself and your control.

Listening is where everything divine truly begins.

The Mount of Transfiguration

We find this idea again in the New Testament, and it led to one of the most revolutionary movements in human history.

In the heart of his ministry, Jesus takes his three closest students with him “up a high mountain” (Matthew 17:1). To their surprise, Jesus is then “transfigured” or unveiled in his radiant glory and “his face shone like the sun” (17:2). (Here I’m reminded of the second essay in this series about seeing the face of the other.) Finally, Moses and Elijah – the ancient Hebrew prophets – appear next to Jesus (17:3).

Peter, Jesus’s lead student, immediately reacts by talking and trying to build boxes around what he is experiencing. He says, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. If you wish, I will put up three shelters – one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah” (17:4)

Peter presumes to already know what is good and how to respond to it. His religiosity did not require the risk of listening. He wants to safely capture and control divine revelation and turn it into something he can manage for himself – literally to build a camp around it.

(Isn’t that precisely the essence of idolatrous religion? “Lord, it is good for us to be here. I will put up shelters around it.”)

But God doesn’t want shelter, and he explodes Peter’s unlistening religion.

First, God speaks from heaven and says, “This is my beloved Son. Listen to him” (17:6). In other words, don’t try to capture this. Just be present, attentive, and ready for what he says – whatever it will be.

Second, Moses and Elijah then disappear (17:8). To the Jewish people, “Moses” represented the Law or the first five books of the Bible, and “Elijah” represented the Prophets or (to oversimplify) the remainder of inspired Scripture.

Together, the text is subtly and subversively saying,

If you want to be ready for the new thing God is doing, you cannot depend on what you already know. ‘Moses’ and ‘Elijah’ are vanishing, and you must not construct a camp around them. Let them go and simply listen to the one I love.

Like the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament is making a radical claim about how an authentic relationship with the transcendent God is possible. First, you must give up assuming that you already know God in the way God wants to be known. And, second, you must be totally vulnerable and listen for God – for whatever God will say.

And thus Christianity was born, and history changed forever.

Idolatry and True Religion

The Bible claims that the simple but profound act of listening – of being open to and attentive for what we do not already know or possess – is the heart of true religion or what it means to be bound to God rather than idols.

Ultimately, idols are safe and attractive precisely because they don’t have anything to say to us and thus don’t require our listening. Instead, idols tell us what we want to hear, since they speak with our own voice. They are a powerful religious technology that earlessly allows us to hear our own opinion as the voice of God.

The irony here is that many of us assume that “religion” is fundamentally conservative and self-protecting. But that is idolatry. The Shema and the Mount of Transfiguration are claiming something intensely counter-cultural: true religion is (1) surprisingly progressive, (2) never exactly settles but always remains open to newness (to God), and thus (3) can sometimes be most faithfully embodied by releasing what was previously grasped as sacred.

In one of his earliest courses at the University of Berlin, Bonhoeffer distilled this radioactive biblical claim like this: “God is always the One who is to come; that is God’s transcendence. One can only have God by expecting God.” Here Bonhoeffer is alluding to the mystery of God’s name revealed to Moses at the burning bush: “I-will-be-who-I-will-be” (Exodus 3:14).

Bonhoeffer unpacks this dense statement and continues,

God must be the One who says, ‘I am the absolute beginning.’ We know about God only when God is the One who speaks… We should begin with God’s own beginning set for us. Nobody knows that in advance; we must each receive it as told us… Deus dixit [God speaks]—to accept this is the beginning of all genuine theological thinking, to allow space for the freedom of the living God.

A few years later in a sermon when German Christianity was Nazifying itself, Bonhoeffer cut to the heart of this listening approach to God and declared, “All our thinking about God must serve only to make us see how completely beyond us and how mysterious God is.” Here Bonhoeffer attacks what he called a “useable Christianity” devoid of “risk-taking,” which could only result in idolatry.

Nazified Christianity was an unhearing idol that told the German people exactly what they were already saying to themselves. And for Bonhoeffer – and for us today – the counter-intuitive starting-point for resisting this grave evil was the same as Moses’s Shema and Jesus’s Mount of Transfiguration: to stop and listen for what God is truly saying beyond our self-idolizing camps.

Everyday Listening as Spiritual Rehab

In conclusion, what I want to suggest is that ordinary listening to other people around us in daily life can serve as a rehab for our ability to listen for God and resist evil in our world.

Think of the simple question, “How are you doing?”

When we genuinely ask this question and stop to listen to the other person’s answer, we practice opening ourselves to transcendence and making ourselves vulnerable to their self-revelation. “How are you doing?” tears us out of our easy assumption that we already know or that it doesn’t matter. And thus listening to their voice exposes us to their previously hidden needs and desires and implicates our responsibility.

For example, I remember asking a friend last year how they were doing. They began to cry and revealed that they were plagued with the thought of suicide. The week before, when they asked for a handful of my aspirin, they were not thinking of killing their pain but killing themself.

My listening question “How are you doing?” led to their self-revealing answer “I’m thinking of killing myself.” And this took me far beyond the acquisition of information to the implication of my responsibility in relationship with my friend: “How can I listen further and love you in the way you need, so you can keep living?”

I’m sobered when I recall that my friend said they had no one else to talk to – no one else to listen to them. Without my open ear, my friend might be dead now, but, thank God, they are alive. I wonder how many lives have been lost because of our lack of listening.

My point here is threefold.

First, listening to others around us re-trains us in being ready to hear what we cannot know by ourselves. It lifts us out of our egocentric ignorance and indifference, and it opens us to transcendence.

Second, listening to others does not merely acquire information but implicates us in response. The other’s self-revelation re-trains our muscles to engage and act with love.

And, third, listening and responding to others rehabilitates our ability to listen and respond to God. Transcendence, revelation, and responsibility are no longer foreign but woven into the fabric of our daily lives with one another through this consistent practice.

Every time we genuinely listen, I believe we are engaging in a spiritual practice of faith that makes us human, connects us to God, and delivers us from death to life. We are interrupting the inertia of our experience, opening ourselves to what transcends us, and waiting patiently for the self-revelation of others, whether our neighbors or God.

Rehab of the Senses is an experiment in overcoming a part-time spirituality for a sacred way of life that that welcomes God into every dimension of our daily experience. Listening is where everything divine truly begins. And we can practice it in our everyday lives with one another, converting our attentive ears into spiritual organs that can heal and open the way for heaven on earth.

Shema. Are we listening?

***

It is essential for all of us to find the nourishment we need in daily life itself… Daily life is only nourishing when we have discovered the wisdom of the present moment and the presence of God in small things. It is only nourishing when we have given up fighting reality and accept it, discovering the message and gift of the moment… Each of these can be an occasion for wonder and awe, a moment of the presence of God.

Jean Vanier, Community and Growth