Dear friends,

How do you celebrate the Fourth of July or a similar patriotic holiday in your national context?

One of my habits is to read Frederick Douglass’s 1852 speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” I consider this one of the most powerful and profound speeches in American history.

I also see it as an enduring paradigm for faithful Christian patriotism today. It shows us how people of faith can wisely commemorate political holidays and relate to their countries. Below, I’ll summarize Douglass’s faithful patriotism as appreciation, confrontation, and aspiration.

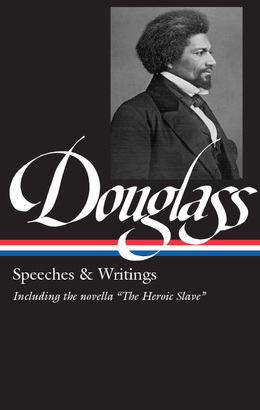

This week, I invite you to spend some time reading or listening to Douglass’s speech. Sadly, both links only offer brief excerpts. The full speech is available in this new collection of Douglass’s writings, which I’ll quote from below: Douglass: Speeches and Writings (New York, NY: Library of America, 2022), edited by David Blight.

In what follows, I offer a brief introduction to Douglass’s life leading up to his historic speech and then unpack it as a paradigm of faithful patriotism.

May freedom flourish!

Andrew

Frederick Douglass’s Context

Frederick Douglass was born in 1818 to an enslaved woman named Harriet Bailey and an unknown white man in Maryland. His father may have been Aaron Anthony, a slave owner, seller, and plantation overseer.

Douglass’s formative years were beset with enormous challenges. He was born into slavery without a father. His mother died when he was eight. His grandmother Betsey started raisin him but then abandoned him. On the Lloyd plantation where he lived, he witnessed enslaved individuals being brutally beaten and whipped.

When Douglass was eight, he was sent to live with a white family, Hugh and Sophia Auld, and there he recalls sleeping on a bed for the first time in his life. When he was nine, Sophia began to teach him how to read, but Hugh stopped him from continuing his lessons because he believed learning made enslaved people rebellious. As a ten-year-old, Douglass heard enslaved people walking in chains as they were transferred by slave traders from local pens to ships. (Hugh was a ship builder.)

By age eleven, Douglass started working as an errand boy for Hugh. He converted to Christianity at age thirteen, joining Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. A beer deliverer and free Black man named Charles Lawson secretly taught Douglass to read the Bible against Hugh’s wishes. Around this time, Douglass started memorizing speeches, learned about the abolitionist movement, and continued secretly educating himself.

During these formative years, Douglass’s family, like many others, was ripped apart by slavery. At least fifteen of his family members were sold off to southern states, and Douglass was threatened with this fate himself. At age fifteen, he started teaching other Black people to read at Sunday school. As punishment, Hugh rented him out as a field worker to Edward Covey, a man known for his brutality who mercilessly whipped Douglass. Nevertheless, Douglass was unconformed. At seventeen, he started another secret reading class at church for around forty other enslaved people.

By eighteen, Douglass made an unsuccessful attempt to escape slavery. After he was caught, he was returned to the Aulds and became a caulker at a shipyard, where he was badly beaten by four white apprentices. Despite his bondage and abuse, Douglass joined the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society to strengthen his speaking skills and continued to teach reading classes for Black people.

In his twentieth year, Douglass successfully escaped from slavery, moved to New York, and married Anna Murray, who escaped from slavery with Douglass’s help. In the North, Douglass applied for jobs using his skill as a caulker. But whites refused to work with a skilled Black person, so he survived by shoveling coal and sawing wood.

Douglass was relentless in his vocation. He deepened his faith and his abolitionist conviction. At twenty-one, his public condemnation of the degradation of Black people was first published in William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator; he was licensed to preach by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church; he registered to vote; and Anna gave birth to their daughter Rosetta.

Douglass soon started working for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society describing his experience as an enslaved person, exposing the evil of slavery, and advocating for abolition. He then became an influential lecturer, writer, and publisher on behalf of abolition, desegregation, and women’s rights. Douglass also actively supported fugitives fleeing from slavery and helped them escape to freedom.

Douglass’s Speech: Appreciation, Confrontation, and Aspiration

This offers brief biographical context leading up to Frederick Douglass’s speech on July 5, 1852 “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Douglass was thirty-four years old and one of the most eloquent advocates for the full equality of all people.

Douglass does many things in this lengthy public discourse before an anti-slavery society. But I’d like to highlight his three core moves as a paradigm for faithful patriotism today: he expresses appreciation for the good, confronts the evil, and aspires for a better future in his society.

Appreciation

Douglass begins his speech by celebrating the freedom that his audience’s ancestors courageously chose for themselves. On July 4th, 1776, they declared that they would become “a sovereign people” and no longer be subjects to a ruler. Douglass hails them for seeing absolutist government for what it was and is: “unjust, unreasonable, and oppressive, and altogether such as ought not to be quietly submitted to” (168).

Still, Douglass notes that, at the time, many people thought independence was a major mistake and even wrong in the eyes of God. They didn’t want change. To claim freedom from the English monarchy risked being labeled “plotters of mischief, agitators and rebels, dangerous men.” The “lovers of ease” and “worshipers of property” wanted the status quo to continue.

All the more, then, Douglass appreciates the revolutionaries’ daring courage:

“To side with the right, against the wrong, with the weak against the strong, and with the oppressed against the oppressor! here lies the merit, and the one which, of all others, seems unfashionable in our day… They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but they knew its limit. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was ‘settled’ that was not right. With them, justice, liberty, and humanity were ‘final’; not slavery and oppression… Of this fundamental work, this day is the anniversary.” (168, 171-172)

For Douglass, this is what should be celebrated on July 4th: putting right over might, principle over power, morality over empire – even when it’s “unfashionable” and costly. With moral passion, he admonishes his audience,

“The Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and against whatever cost… Cling to this day.” (170)

Douglass could have concluded his speech right here, and many Americans would consider his work done and his patriotism complete. But Douglass had a much fuller vision of patriotism, and he sharply notes, “as a people, Americans are remarkably familiar with all facts which make in their own favor” (172). In other words, Americans only like to hear positive things about themselves.

Confrontation

Douglass’s appreciation of America was simultaneously the fuel for his confrontation of America. In light of July 4th, white Americans inflicted upon people of color the very thing that they condemned as intolerable for themselves – enslaving oppression. Rather than making the hard choice for fundamental change, they stopped short and accepted continuing as oppressors.

From the start of his speech, Douglass subtly signals this scathing confrontation. He speaks of “your National Independence,” “your political freedom,” “your great deliverance.” He interrogates, “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us [Black people]?” (174).

Douglass’s life was an irrefutable negative answer to this question. He continues,

“The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn…

Fellow-citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them… To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world. My subject, then fellow-citizens, is AMERICAN SLAVERY. I shall see, this day, and its popular characteristics, from the slave’s point of view.” (174, 175)

This is exactly what the rest of Douglass’s speech does: he sees July 4th from the perspective of the oppressed. And what Douglass observes is clear:

“Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.” (175)

Douglass makes this claim based on his compelling critique of American law, culture, and religion rooted in commonsense, Christian ethics, and comparison with other societies. He details white Americans’ “wicked indifference” to Black children’s suffering, the abuse of women, and the breakup of families in the name of hypocritical freedom and immoral profit.

Douglass’s conclusions are a bitter pill for some Americans to swallow, but they match the evidence he presents: “Your Christianity is a lie… [The founding fathers] were the veriest imposters that ever practiced on mankind” (188).

The purpose of Douglass’s confrontation is not a dead-end of shame but a call to abandon national self-righteousness and to face the truth: “the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced” (178).

As a Christian, I am particularly moved by Douglass’s Christian critique of white American Christianity. He examines how popular theology was twisted to justify slavery and how Christian leaders became “the champions of oppressors.” He also points out that if churches and Christian organizations came together to condemn slavery, it could never have survived in America. “And that they do not do this involves them in the most awful responsibility of which the mind can conceive” (185).

It is on this basis that Douglass, a Christian minister, says with grief,

“your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to [the oppressed] mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy – a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages… this horrible blasphemy is palmed off upon the world for Christianity…

They strip the love of God of its beauty and leave the throne of religion a huge, horrible, repulsive form. It is a religion of oppressors, tyrants, man-stealers, and thugs…

Your Christianity is a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad; it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing, and a byword to a mocking earth.” (178, 183)

One hundred and seventy-one years later, Douglass’s confrontation prompts us to ask hard questions of ourselves today:

- Who in our society is not fully included in the the proud “we” with which “we hold these truths” of human freedom? What is the Fourth of July to them?

- What “blessings” are not “enjoyed in common”? What “mournful wails” are muffled by one-sided “joys”?

- How are Christians still “chiming in with the popular theme” and refusing the unpopular responsibility of confronting hypocrisies, inequities, and injustices as God demands?

Aspiration

As a survivor and opponent of American slavery, Douglass was anything but naive. He admitted, “The eye of the reformer is met with angry flashes, portending disastrous times.” Many people didn’t want change. Still, Douglass didn’t stop with confrontation or crumble to hopelessness. He believed a better future was possible and concluded,

“I do not despair of this country… ‘The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.” (190)

Like his confrontation, Douglass’s aspiration for a better future was also rooted in his opening appreciation for July 4th. The founding value of “siding with the right, against the wrong, with the weak against the strong, and with the oppressed against the oppressor” is real and worth building upon. This moral vision can still be reclaimed to guide society into the future.

As a Christian, Douglass didn’t hold utopian illusions of a perfect society. Still, he believed that accountability and improvement were possible within an increasingly connected world. And so he ends his passionate speech with an equally passionate prayer to God and a promise to relentlessly work for equal human freedom, reconciliation, and justice – “whatever the peril or the cost” (192).

A Paradigm of Patriotism

Frederick Douglass offers us a powerful paradigm for faithful patriotism today. He refuses the easier options of only seeing the good, only seeing the evil, or only looking to a better future in our society. Douglass does all three.

First, Douglass expresses his appreciation for the freedom that American independence set in motion. He celebrates the good – in this case, the courage to refuse absolutist rule and struggle for democratic self-government.

Second, Douglass boldly confronts the fundamental hypocrisies and racial injustices entrenched in American society. He rejects blind nationalism and demands a truthful patriotism that exposes and condemns national evils.

Third, Douglass articulates his aspiration for an improved society where the God-given rights of all people are recognized and respected. With appreciation and confrontation, Douglass calls us to work together for a better future.

In our time of clashing identities and increasing polarization, Frederich Douglass embodies a more complex and faithful patriotism. He invites us to take seriously the pride, pain, and possibility of our full humanity.